Of all the kinds of bacteria, some are charming and beneficial, others are malicious and dangerous—and then there are the ones that are just plain turds.

That’s the case for Mycoplasma hyorhinis and its ilk.

Researchers caught the little jerks hiding out among cancer cells, gobbling up chemotherapy drugs intended to demolish their tumorous digs. The findings, reported this week in Science, explain how some otherwise treatable cancers can thwart powerful therapies.

Drug resistance among cancers is a “foremost challenge,” according to the study’s authors, led by Ravid Straussman at the Weizmann Institute of Science. Yet the new data suggest that certain types of drug-resistant cancers could be defeated with a simple dollop of antibiotics alongside a chemotherapy regimen.

That said, the findings are still mostly from lab and animal experiments. It will be a while before the results are repeated and confirmed in human cancer cases, then possibly translated into new clinical practices for treating certain types and cases of cancers.

Dr. Straussman and his colleagues got a hunch to look for the bacteria after noticing that, when they grew certain types of human cancer cells together in lab, the cells all became more resistant to a chemotherapy drug called gemcitabine. This is a drug used to treat pancreatic, lung, breast, and bladder cancers and is often sold under the brand name Gemzar.

The researchers suspected that some of the cells may secrete a drug-busting molecule. So they tried filtering the cell cultures to see if they could catch it. Instead, they found that the cell cultures lost their resistance after their liquid broth passed through a pretty large filter—0.45 micrometers. This would catch large particles—like bacteria—but not small molecules, as the researchers were expecting.

Looking closer, the researchers noticed that some of their cancer cells were contaminated with M. hyorhinis. And these bacteria could metabolize gemcitabine, rendering the drug useless. When the researchers transplanted treatable cancer cells into the flanks of mice—some with and some without M. hyorhinis—the bacteria-toting tumors were resistant to gemcitabine treatment.

-

Bacteria (in green) inside a pancreatic cancer cell of the AsPC1 pancreatic cancer cell line. The nucleus of the cancer cell is in blue.Leore Geller

-

Bacteria (in green) inside a pancreatic cancer cell of the AsPC1 pancreatic cancer cell line. The nucleus of the cancer cell is in blue.Leore Geller

-

Bacteria (in green) inside a pancreatic cancer cell of the AsPC1 pancreatic cancer cell line. The nucleus of the cancer cell is in blue.Leore Geller

-

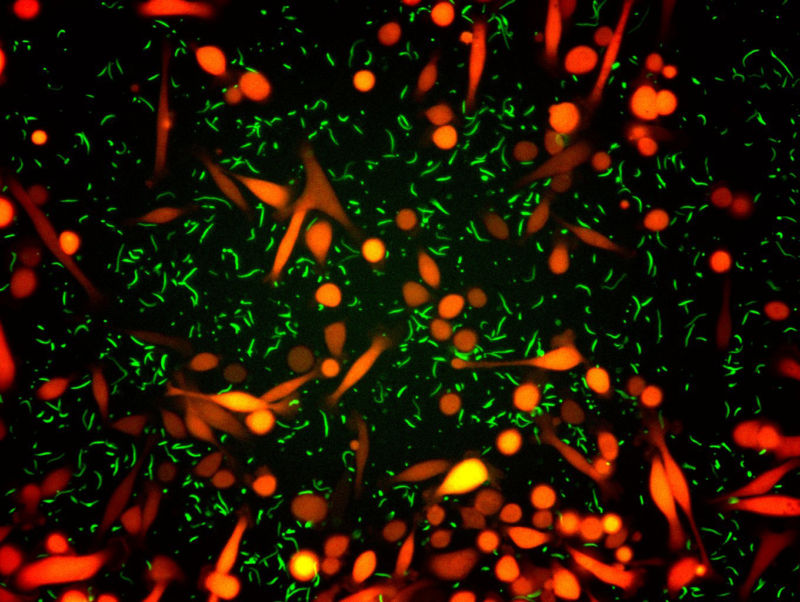

An example of an experiment where bacteria (green) and cancer cells (red) are co-cultured.

And it’s not just M. hyorhinis that can turn tumors resistant. When the researchers pinpointed the gene that encodes the molecular machinery for disarming gemcitabine in M. hyorhinis—a gene called CDDL—they found that it’s quite common in other bacteria. In initial testing of 27 bacterial species, 13 could knock out gemcitabine. When the researchers searched through the genetics of nearly 2,700 bacteria, they found that hundreds also had the gene for defeating gemcitabine. Most of those bacteria were in the Gammaproteobacteria class, a giant group of bacteria that includes E. coli and Salmonella.

To see if this may be a real problem in humans, the researchers gathered 113 cell samples from human pancreatic cancers (a cancer type called pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma). These were all collected during cancer surgeries. The researchers also assembled 20 samples from organ donors that had non-cancerous pancreases (or “pancreata,” if we're being persnickety). Of the 113 cancer samples, 86 had signs of bacteria present—mostly Gammaproteobacteria—while only three of the 20 non-cancerous samples had bacteria.

The researchers speculate that bacteria may invade pancreatic tumors by migrating from the duodenum, the top section of the small intestine.

To put all their findings together, the researchers engineered an E. coli strain to carry CDDL—a gene it didn’t carry before—then injected the strain into tumor-riddled mice. The researchers used fluorescent markers to track both the bacteria and the tumors. When they treated the mice with either gemcitabine and an antibiotic or just gemcitabine alone, they saw bacteria disappear and tumors shrink in the mice that got the antibiotic-chemotherapy combo. But in the mice with just chemotherapy, the researches saw rapid tumor progression.

The role of bacteria in drug-resistant cancers and the potential for using antibiotics with chemotherapies “merit additional exploration,” the authors conclude.

Science, 2017. DOI: 10.1126/science.aah5043 (About DOIs).

reader comments

50