A white Brit writing from the point of view of an African American has a duty to get it right. Research for my novel Buffalo Soldier (set in the USA during and after the Civil War) involved reading slave testimonials and the autobiographies of – amongst others – the African American abolitionists Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman.

So re-reading To Kill a Mockingbird this year, in preparation for running a Reading Workshop at the Edinburgh International Book Festival, was a very different experience to the one I’d had as a teenager. This time I saw Maycomb, Alabama from a completely different perspective.

I – like so many other people – fell in love with the book when I studied it for O Level (GCSE). It’s a masterpiece: there’s no doubt about that. But it’s not as morally simple or straightforward as I once thought.

As a child, stories taught me that the bad guys always get caught and the good guys always have a happy ending. To Kill a Mockingbird was the first book I came across that showed me that guilt or innocence is immaterial if the system is stacked against you. Racism is like sexism; if you’re not on the receiving end you simply don’t see it. As a white teenager growing up in a white town it was my first encounter with the issue.

To Kill a Mockingbird started me thinking.

But did it make me think enough?

Harper Lee’s focus is purely white. Given that her narrator is a child growing up in the 1930s segregated South, maybe that’s inevitable. Perhaps nothing else would be plausible. But one of the book’s central themes is that you need to walk around in someone else’s skin to understand them and Harper Lee doesn’t actually get under the skin of any of the black characters.

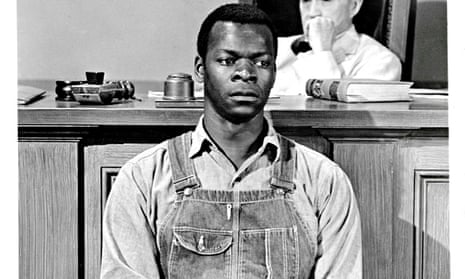

The closest we get is Calpurnia, the family’s cook, but we never know what she’s thinking or feeling. Only once does she express an opinion – an event so startling that Scout remarks on it. Calpurnia is in the fictional tradition of the “happy black”, the contented slave – the descendent of the ever-loyal Mammy in Gone With the Wind. And the rest of the black community is depicted as a group of simple, respectful folk – passive and helpless and all touchingly grateful to Atticus Finch – the white saviour. We never see any of them angry or upset. We never see the effect of Tom Robinson’s death on his family up close – we don’t witness Helen, Tom’s wife, grieving and Scout never wonders about his children. Their distress is kept at safe distance from the reader.

Although the book touches on the horrors of racism in the Deep South, it’s a strangely comforting read. A terrible injustice is done, but at the end the status quo is reassuringly restored. The final message is that most (white) people are nice when you get to know them. The book closes with Atticus sitting by Jem’s bed, solid and safe and reliable. As readers, we can all sleep easy in our beds because the father figure is watching over us. As readers we remain in a state of childlike innocence.

When I suggested to the group in Edinburgh that maybe, possibly, To Kill a Mockingbird might be considered a profoundly racist novel there was a collective sharp intake of breath and some very stony stares. But what followed – once they’d recovered from the shock of having a beloved book described that way – was an extremely considered and thoughtful discussion. Of course, it helped that Go Set a Watchman had been published by then. The book Harper Lee had originally set out to write is a slap in the face not only for Scout but for white society as a whole.

It’s a discussion I’ll be continuing over the coming year in schools who have invited me to speak on the subject. Racism is not a thing of the past that was solved back in the 1930s by Atticus Finch. Slavery has cast a very long shadow and we are all still living with the consequences. Writing Buffalo Soldier has led to the most extraordinary conversations with people of all ages. Talking about these things can be difficult, but we shouldn’t shy away from them. To Kill a Mockingbird gives an insight into the subject, but the way in which it is still read demonstrates that we have a very long way to go before we can declare ourselves to be truly “colour blind”.

Tanya Landman’s latest Buffalo Soldier won the Carnegie medal 2015, her latest book is Hell or High Water