E n D ®

E n D ®

E n D ®

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

E n D <strong>®</strong><br />

11-13 İL SDDV<br />

DAİ ITH DIBDRDERS DESİG DISCOURSE, DISASTE<br />

Edited by:<br />

TevfîkBALCİOĞLU<br />

Özlem ÇAĞLAR TOMBUŞ<br />

Derya IRKDAŞ

This EAD07 Proceedings 2007 edition published by Izmir University of Economics<br />

Address: Sakarya Caddesi No:156 Baîçova, İzmir-TURKEY<br />

Teİ:+90 232 2792525<br />

Fax: +90 232 2792626<br />

Website: http://www.ieu.edu.tr<br />

Copyright © İzmir University of Economics<br />

Ali rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any<br />

means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.<br />

ISBN: 978-975-8789-21-4<br />

EDITORS: Tevfik BALCIOĞLU<br />

Özlem ÇAĞLARTOMBUŞ<br />

Derya IRKDAŞ<br />

DESIGNER: Derya IRKDAŞ<br />

Printed and bound in TURKEY<br />

Produced by Yılmaz Sürekli Form ve Matbaacılık, Engin YILMAZ<br />

Address: 2826 Sokak No: 52 Kat 3/301 1. Sanayi Sitesi, İzmir - TURKEY<br />

Tel:+90 232 4599600<br />

Conference website: http://fadf.ieu.edu.tr/ead07

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

We are grateful to those who have supported the EAD07 Conference:<br />

IZMIR UNIVERSITY OF EGDNDMICS<br />

TÜBİTAK<br />

Ekrem Demirtaş, President, Board of Trustees of IDE<br />

i I Prof. Dr. Attila Sezgin, Rector of IDE<br />

Photograph by Güven İncirlioğlu<br />

EAD Local organizing comittee, EAD Comittee, Reviewers, Authors, Assistants, Student Assistants, Technicians, ELDA, XXI.

LOCAL ORGANIZING COMMITTEE<br />

A. Can Özcan<br />

Artennis Yagou<br />

Christopher S. Wilson<br />

Gülsüm Baydar<br />

Hakan Ertep<br />

Markus Wilsing<br />

Özlem ÇağlarTombuş<br />

Şölen Kipöz<br />

TevfikBalcİoğlu<br />

EAD COMMITTEE<br />

A. Can Özcan,Turkey<br />

Anna Calvera, Spain<br />

Artemis Yagou, Greece<br />

Brigitte Borja de Mozota, France<br />

Deana Mcdonagh, USA<br />

Hans K. Hugentobler, Switzerland<br />

Jacqueline Otten, Germany<br />

John Wood, UK<br />

Julian Malins, UK<br />

Lisbeth Svengren, Sweden<br />

Rachel Cooper, UK<br />

Silvia Pizzocaro, Italy<br />

Stuart Walker, Canada<br />

Tevfik Balcı oğlu, Turkey<br />

Toni-Mattl Karjalainen, Finland<br />

Tore Kristensen, Denmark<br />

Vasco Branco, Portugal<br />

Wolfgang Jonas, Germany<br />

INTERNATIONAL ADVISORY BOARD<br />

Alain Findeli, France<br />

Alpay Er, Turkey<br />

Anna Calvera, Spain<br />

Artemis Yagou, Greece<br />

Brigitte Borja de Mozota, France<br />

DagmarSteffen, Germany<br />

Deana Mcdonagh, USA<br />

Dirk Baecker, Germany<br />

Eckard Minx, Germany<br />

Fatlma Pombo, Portugal<br />

Fatina Saikaly, Italy<br />

Fatma Korkut,Turkey<br />

Franz Liebl, Germany<br />

Füsun Curaoğlu, Turkey<br />

Gülay Hasdoğan, Turkey<br />

Hakan Ertem, Turkey<br />

Hans Dehlinger, Germany<br />

Hans Kaspar, Switzerland<br />

Harold Nelson, USA<br />

John Broadbent, Australia<br />

John Langrish, UK<br />

Kari-Hans Kommonen, Finland<br />

Keith Russell, Australia<br />

Ken Friedman, Norway<br />

Klaus Krippendorff, USA<br />

Lisbeth Svengren, Sweden<br />

Maria C. L dos Santos, Brazil<br />

Maren Lehmann, Germany<br />

Matthias Gotz, Germany<br />

Michael Erihoff, Germany<br />

Mike Press, UK<br />

Mine Ertan, Turkey<br />

Nigan Bayazit, Turkey<br />

Ozlem Er, Turkey<br />

Rachel Cooper, UK<br />

Ranulph Glanville, UK<br />

Rosan Chow, Germany<br />

Silvia Pizzocaro, Italy<br />

Terence Love, Australia<br />

Uta Brandes, Germany<br />

Uwe von Loh, Hofthiergarten<br />

Tore Kristensen, Denmark<br />

Vasco Branco, Portugal<br />

Wolfgang Jonas, Germany<br />

Zuhal Ulusoy, Turkey<br />

EXTENDED LIST OF REVIEWERS<br />

Ali Cengizkan, Turkey<br />

Aren Emre Kurtgözu, Turkey<br />

Bahar Şener, Turkey<br />

Bernhard Rothbucher, Austria<br />

CliveDilnot,USA<br />

Daniela Sangiorgi, Italy<br />

Deniz Güner, Turkey<br />

Deniz Hasırcı,Turkey<br />

Eduardo Corte Real, Portugal<br />

Francesc Aragall, Spain<br />

Gül Kaçmaz Erk,Turkey<br />

Güven İncirlioğlu,Turkey<br />

Hakan Edeholt, Sweden<br />

Hilary Cunliffe-Charlesworth, UK<br />

JillyTraganau, USA<br />

Martyn Evans, UK<br />

Miodrag Mitrasinovic, USA<br />

Naz A.G.Z. Börekçi, Turkey<br />

NecdetTeymur, UK<br />

Nur Demirbiiek, Australia<br />

Oya Demirbiiek, Australia<br />

Philippe Gauthier, Canada<br />

Rabah Bousbaci, Canada<br />

Sara llstedt Hjelm, Sweden<br />

Suat Günhan, Turkey<br />

Tiiu Poldma, Canada<br />

Tomas Dorta, Canada<br />

Ulla Johansson, Sweden<br />

CONTRIBUTERS<br />

Alessandro Segalini<br />

Alkin Korkmaz<br />

Angela Burns<br />

Aslı Çetin<br />

Aylin Mavioğlu<br />

Bahar Kürkçü<br />

Berna Yaylalı Yıldız<br />

Burkay Pasin<br />

Christopher S. Wilson<br />

Deniz Hasircİ<br />

Duygu Kocabaş<br />

Elif Kocabiyik<br />

Ertan Demirkan<br />

Eser Selen<br />

Sonay Perçin<br />

Suat Günhan<br />

Tuna Yılmaz<br />

Xander Van Eck<br />

Zeynep Tuna Ultav<br />

Zuhal Ulusoy<br />

ASSISTANTS<br />

Argun Tanrıverdi (Photographer)<br />

Bahar Emgin<br />

Gülden Canol [Photographer)<br />

Sonay Ş. Perçin<br />

TECHNICIANS<br />

Eser Sivri<br />

Ünal Çiçek<br />

VİDEO<br />

Erkin Araz<br />

...and ali student assistants

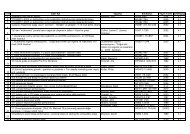

INDEX<br />

Introduction 12<br />

Keynote Speakers: Eİif Akarlilar, Ayşe Birsel, Clive Dilnot and Gert Dumbar 14<br />

Theme: Discourse<br />

"I want disorder - get it?":The paradoxical representations in contemporary architectural narratives 17<br />

AçalyaAlImer<br />

On the relevance of blind-variation-and-selective-retention in creative architectural problem solving within the context of 23<br />

architectural education<br />

Hakon Anay<br />

Computer aided design (cad) and computer aided manufacturing (cam) in the jewellery sector in Turkey 28<br />

Dilek Ayyildiz<br />

From chaos to clarity: the central role of the designer's appreciative system in design activity 36<br />

Monique Josephine Bade<br />

New categorization for a virtual on-line poster museum 47<br />

Heieno Borbosa, Anna Calvera, Vosco Branco<br />

Developing the brand of a born global company from Turkey as a newly Industrialized country: The Gala&Gino case, 58<br />

İrem Bektoş, Özlem Er<br />

Directive, discreet, discriminatory: Modern signage and the design of gender 69<br />

Pedro Besso<br />

Crazy ideas or creative probes?: Presenting critical artefacts to stakeholders to develop innovative product ideas 77<br />

Simon John Bowen<br />

Competing with global players: The other side of the coin 87<br />

Suzan Boztepe<br />

The question of design aesthetics: Some thoughts on its formulation nowadays 98<br />

Anna Colvera<br />

Cultural diversity In product design and product usability 110<br />

Henri Christiaons, Jan Carel Diehl<br />

Dancing with design - a study of the national design policy and design support programmes in South Korea 118<br />

Young Ok Choi, Rachel Cooper, Sungwoo Lim<br />

Re-assessing assessment practices in design to support students' long-term learning 129<br />

Teena Clerke<br />

An alternative method of communication between client and designeratthe"fuzzy front end" of the design process 145<br />

Deborah Camming<br />

The role of the learning context and designer characteristics challenge and reveal the design process 155<br />

Nur Demirbiiek, Dianne Joy Smith, Andrew Scott, LesDawes, Paul Sanders<br />

Design intensive born global companies in Finland: Challenges of the designer as entrepreneur 168<br />

Zeynep Falay<br />

Sustainable design: A critique of the current tripolar model 179<br />

Alain Findeli<br />

The balancing act of product discourse and performance 190<br />

Josiena Gotzsch

"Interfaces of the real": Semantic discourse of object and consumption in interactive product design 199<br />

Ateş Gürşimşek<br />

Sustainable fashion 207<br />

Li Han<br />

Controlled disorder: Mental imagery and external representation in the creative design process 213<br />

Deniz Hasırcı<br />

Service-scape and white space: White space as a structuring principle in service design 224<br />

Stefan Hoimlid, Anni{

Signs of discourse: Site markers as places of cultural negotiation in Ladakh, India 409<br />

Angela Norwood<br />

How to add cultural attributes to the design process of a digital video library's user interfaces 414<br />

Metin Çavuş, Oğuzhan Özcan<br />

Lean design discourse: Searching for structure and eliminating waste in design 421<br />

Şule Taşlı Pektaş<br />

Cultural product design 428<br />

İrini Pitsoki<br />

Order, disorder, complexity 441<br />

Silvia Pizzocaro<br />

Drawing and images of design. Representation and meaning. 448<br />

Fdtima Pombo, Graça Magalhâes<br />

Strictly ballroom or dancing in the moment? Methods for enhancing the partnership of design and business 458<br />

Emma Murphy, Mike Press<br />

Today's illustration. Representations of a designer's way of design thinking 469<br />

Joana Quental, Fdtima Pombo<br />

An exploratory study of fashion design: Designer, product and consumer 477<br />

Osmud Rahman, Xiuli Zhu, Wing-sun Liu<br />

A footwear design project as a design discourse 488<br />

Seçil Şatır, Demet Günal Erîaş, Deniz Leblebici<br />

Designer's metis 498<br />

Osman Şişman<br />

From the universal to the particular: Emotional responses to pattern 507<br />

Frances Stevenson<br />

Limited utterances within journals: The functionality of architectural discourse on earthquake as disaster 515<br />

Zeynep Tuna Ultav<br />

An un-natural world:The designer as tourist 527<br />

Viveka Turnbull Hocking<br />

Devising the plot: Communicating designers thinking through storytelling 537<br />

Louise Valentine<br />

Design redux 544<br />

Stuart Walker<br />

Dancing with disorder: Synergizing synergies within metadesign 554<br />

John Wood<br />

Discourse through making:The role of the designer-researcher in eliciting knowledge for interactive media learning resources 563<br />

to support craft skills learning<br />

Nicola Wood<br />

Beyond disaster: On establishing a Greek-Turkish design research programme 572<br />

Artemis Yagou<br />

A general look at cross-cultural usability methods applied in interactive interface design: Localisation and Turkey 579<br />

Asım Evren Yantaç, Oğuzhan Özcan<br />

Intelligent product designs that involve convergence of multiple technologies: The examination of relevant applications in 586<br />

Turkey<br />

Sıla Yiğit

Technomethodology: Interface design as a hybrid discipline between system design and ethnomethodology 599<br />

Victor Zwimpfer<br />

Theme: Disorder<br />

Order and disorder in keyboards - IVlemetics of typing 608<br />

Aysur) Aytaç<br />

The dance of disorder: Can an understanding of chaos and fragmentation lead to a design approach for a socially inclusive 623<br />

public realm?<br />

Bradley Braur)<br />

Objects for peaceful disordering: Indigenous designs and practices of protest 632<br />

Tom Fisher<br />

Killer products in the market ecosystem, the role of design in killer products 642<br />

Melehat Nil Gülari<br />

Periodization in a research on the history of design in Turkey 653<br />

Gülname Turan<br />

The parody of the motley cadaver: Displaying the funeral of fashion 660<br />

Robyn Fieaİy<br />

How often do you wash your hair? Design as disordering: Everyday routines, human object theories, probes and sustainabillty 668<br />

Sabine Hielscher, Tom Fisher, Tim Cooper<br />

Overcoming the mental barrier: Social and environmental responsibility in design from a newly industrialized country 679<br />

perspective<br />

Çiğdem Kaya, Özlem Er<br />

Harnessing disorder and disaster in responsive narrative systems 688<br />

Donna Roberta Leishman<br />

Design against and for crime in urban life: Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (CPTED) versus Design for Crime 699<br />

Deniz Deniz, A. Can Özcan<br />

Cities and the destruction of human identity 704<br />

Michelle Ann Pepin<br />

Inventing design idioms from the plurality of identities in South Africa 712<br />

Phillip John du Plessis<br />

Social mobiles and speaking chairs: Applying critical design to disruption, discourse and disability 726<br />

Graham Pullin<br />

Naqqal's gifts: The affects of external dynamics on computer games 733<br />

Tongue Ibrahim Sezen, Diğdem Işıkoğlu<br />

Design as a negotiator between self and its world - towards a reasonable state of disorder 743<br />

Ahmet Zeki Turan<br />

Dancing with displacement: The conditions of displacement in Athens 752<br />

EleniTzirîzilaki<br />

Social responsibility of design; contribution of design in development of national industry and economy 760<br />

Selen Devrim Ülkebaş<br />

Designer and consumer as victims in consumption culture 772<br />

5. Selhan Yalçın Usal

Theme: Disaster<br />

Design against disaster: Siıİftİng lifestyles to prevent environmental disaster 780<br />

Ln. EceAnburun<br />

The life cycle assessment of temporary housing 789<br />

Hakon Arslon<br />

Design disasters In the history of computing 797<br />

Paul Atkinson<br />

How to design for the base of the pyramid? 807<br />

Jan Corel Diehl, Henri Christiaans<br />

A local analysis of a global challenge; A step towards understanding mobile phone choice ofTurkish university students 813<br />

Mehmet Dönmez, Nigan Bayazit<br />

Postwar visions of apocalypse and architectural culture: The architectural review's turn to ecology 821<br />

Erdem Erten<br />

Liberty versus safety: A design review 831<br />

Adam Thorpe, Lorraine Gamman<br />

Fear and knowing: Design disasters 846<br />

Neal Haslem<br />

Darwinian Change: Design from Disaster 856<br />

John Z, Langrish<br />

The invisible shades of disorder 862<br />

Raja Mohanty<br />

Representing disaster: Significance of design in communicating social responsibility 871<br />

Şebnem Timur Öğüt, Hümanur Bağlı<br />

Does color drift design to disaster? 877<br />

Tülay Özdemİr Canbolat<br />

Fights and fires are the flowers of Edo 883<br />

Jennie Tate<br />

Profit from paranoia - design against'paranoid'products 894<br />

Lorraine Gamman, Adam Thorpe<br />

Information for people about medicines: Why is it so difficult to swallow? 910<br />

Karel van der Waarde<br />

Picturing and memorializing disaster in Japan: Visual responses to the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 916<br />

Gennifer Weisenfeld<br />

Visualising disaster: Environmental anxiety and the urban imaginary 922<br />

William M. Taylor, Michael P. Levine

European Academy of Design<br />

INTRDDUCTIDN<br />

The 7th Conference of the European Academy of Design took place on 13-15 April 2007 in Izmir, Turkey and was organised by Izmir<br />

University of Economics, Faculty of Fine Arts and Design. The context for the conference, the people involved and the themes are<br />

summarised below.<br />

The European Academy of Design (EAD) was formed in 1994 by a group of leading academics from around Europe to promote<br />

the publication and dissemination of research in design through conferences hosted by different educational institutions in<br />

Europe. EAD has also undertaken the publication of proceedings, newsletters and a journal, to improve European-wide research<br />

collaboration and dissemination. Although the word European sounds limiting, it has in face gone beyond the boundaries of Europe<br />

and contributors from all around the worid have always been welcome. For Instance, at the Izmir Conference, 12% of the speakers<br />

were from outside of Europe. This suits the aims of the EAD well, which are to encourage discussion across traditional boundaries<br />

between practice and theory, and between disciplines defined by working media, materials and areas of application.<br />

The Academy is headed by a committee of acknowledged academics from across Europe, as well as from the United States and<br />

Australia. The Academy has organised six International conferences organized every two years since 1995. The conferences previous<br />

to 2007, their locations, organisers and themes are listed below:<br />

1995 Salford, University of Salford (Rachel Cooper) UK: Design Interfaces<br />

1997 Stockholm, University of Stockholm (Elisabeth Svengren) Sweden: Contextual Design<br />

1999 Sheffield, Sheffield Hallam University, (Mike Press) UK: Design Cultures<br />

2001 Aveiro, University of Averio, (Vasco Branco) Portugal: Desire - Designum - Design<br />

2003 Barcelona, University of Barcelona (Anna Calvera) Spain:Techne: Design Wisdom<br />

2005 Bremen, University of Bremen (Wolfgang Jonas) Germany: Design - System - Evolution<br />

The Conference Theme<br />

Three thematic components of this design conference-disaster, discourse and disorder - indicate three interrelated but relatively<br />

autonomous fields that highlight various aspects related to contemporary issues in design. As one of the most ambitious design<br />

faculties In the country, the organising team in Izmir decided to choose an equally ambitious title for the conference.'Dancing with<br />

Disorder: Design, Discourse, Disaster'. The team particularly like the dances of the'capital' Ds In the title, but the selection was not<br />

accidental. Although no one never wishes it to happen, there are signs that human beings will face different kind of disasters in this<br />

century varying from terrorist attacks to global warming, from tsunamis to scarcity of water. We as designers have a duty, amongst<br />

others, to contribute to the prevention of disasters when possible, to alleviate any pain and to repair the damage.<br />

Definitions of design, a well-known and studied concept, include such terms as "plan," "purpose," "intention" and "function," In<br />

addition to others such as "artistry" and "creativity" that take central importance in the definition of art. Plan, purpose, intention<br />

and function are concepts related to predictability and hence systematic thinking. Systematic thinking in turn is related to order.<br />

Design brings order to the relationship between us and the objects that we use, see and perceive.

Design discourse involves the current language of design, i.e., the terms with which we conceptualise and talk about design.<br />

Design management, design research and current issues in design are some of the specific topics that can be addressed within<br />

this framework. This area of the conference included presentations that sought to go beyond the over-asked question of'what is<br />

design?'and advocate a re-appraisal of accepted design conventions. The role/position of design was particularly scrutinized from<br />

the viewpoint of design research, design and everyday life, images and representation, new materials and methods, and design<br />

management.<br />

Order, on the other hand, suggests a straightening out so as to eliminate confusion. The function of design then, is to eliminate<br />

disorder, i.e., confusion, chaos, unpredictability. All of this is based on a binary thinking which privileges purpose over idleness,<br />

function over dysfunction and order over disorder. Order is a desirable attribute, the failure of which ends up in disaster. But how<br />

are order and disorder defined at first place; by whom; on what basis; and In whose interests? What is the price that is paid in order<br />

to establish order and who pays for it? Is order a historical concept having acquired different meanings in different contexts? If<br />

so, what is the order of today's world, bodies, objects? Is it one or many or have we lost our sense of existence based on plan,<br />

predictability and order? What is the meaning and role of design in relationship to changing notions of order? All these questions<br />

are historical as well as universal to examine crucial relations at any given time.<br />

What can design do for physical and mental disorders: Dysfunctional bodies, schizophrenia and hysteria. How can design contribute<br />

to the end of social disorders, unrest, upheavals, wars, vandalism, crime, domestic violence and so on. How can design counteract<br />

virtual disorders: viruses, hacking, fake identities, deceptive information and information pollution.... Disaster is related to order<br />

because disaster may be defined as the breaking down of order. Presentations that were included In this theme addressed specific<br />

contexts when notions of order, control, social hierarchy and unity are rendered irrelevant. Like order, the identification of disaster<br />

may too be dependent on context. What counts as disaster for a particular culture, group or society may be regarded as victory<br />

for another. Also, disaster may be seen as a precondition for the birth of novelty, especially in the field of design. Hence the<br />

questions range from "what counts as disaster in design?" to "what is the place of design in a world of disasters?" The relationship<br />

between discourse, disaster, disorder and design calls for multi-disciplinary approaches and can be addressed from a variety of<br />

diverse theoretical perspectives such as science, metaphysics, phenomenology, post-structuralism, feminist and psychoanalytical<br />

theories, anthropology, evolutionary approaches, management, etc.<br />

Papers in this volume address contemporary or historical situations from clearly stated research experiences. Naturally, they do<br />

not respond to all of the questions raised above, but illustrate a convincing list of variety that design has much to contribute to this<br />

process - one of the reasons why we are publishing this book.<br />

Prof. Dr. Tevfik BALCIOGLU<br />

Dean, Faculty of Fine Arts and Design<br />

Izmir University of Economics, Izmir, TURKEY

Elif AKARLILAR<br />

'Designing Maviterrenean'<br />

Elif Akarlilar (1969) studied at the University of Vienna and received her post-graduate degree in International Politics. She then<br />

joined International Human Rights seminars at Strasbourg University. As she worked for Mavi New York offices she completed her<br />

masters degree in the New York University in the Costume History field.<br />

In 1991, Elif Akarlilar started to work for her family company in the foundation process of Mavi Jeans brand. Since 1999 she has<br />

been working as the Global Brand Manager at the Istanbul and New York offices of Mavi Jeans. She acts as the creative head of the<br />

brand by managing the design teams in Istanbul and NY as well as the marketing and visual merchandisng teams. Her longtime<br />

collaboration with Adriano Goldschmied, known as the gold hand of jeans design, and her other projects including Rıfat Özbek for<br />

Mavi, Maviology magazine, Martin Parr's'Style Hunting in Istanbul'Photo-book, Organic Denim and Istanbul T-shirts all bear her<br />

signature.<br />

Designer, Birsel + Seek<br />

Ayşe BİRSEL<br />

'My Disorderly Mind'<br />

Ayşe Birsel grew up in Izmir, Turkey. In 1989 she received a Fulbright Scholarship to complete her Master's Degree at Pratt<br />

Institute, Brooklyn, NY<br />

Recipient of the 2001 Young Designer Award from the Brooklyn Museum of Art, Birsel was a finalist at the Cooper Hewitt National<br />

Design Awards In 2002. She was named a Fellow at the International Design Conference at Aspen, and has taught at Pratt Institute.<br />

Her work is in the permanent collections of Cooper Hewitt National Design Museum and the Museum of Modern Art. In 2002, a<br />

collaboration with Bibi Seek led to the creation of their studio Birsel -i- Seek. Fueled by curiosity, disrespect for existing solutions and<br />

a love for drawing as a way to think, they have designed products for Herman Miller, Hewlett Packard, HBF, Merati, Target and Acme.<br />

Their work was included in the National Design Triennial 2006.

CliveDILNOT<br />

'Dancing with Disorder: Design and the Overcoming of Disaster'<br />

Clive Dilnot is currently Professor of Design Studies at New School University, New York where he teaches both design and in the<br />

University Humanities program. Previously, he was Professor of Design Studies and Director of Design Initiatives at the School of the<br />

Art Institute of Chicago. He has also taught at Harvard University, in Hong Kong and in Britain, and has been a visiting Professor at<br />

the University of Technology, Sydney, the University of Illinois in Chicago and Rhode Island School of Design. Dilnot has lectured,<br />

given keynote addresses and acted as visiting critic at universities and conferences world-wide. He has written extensively on design<br />

history and theory. Recent publications include Ethics? Design? {Chicago, 2005) and a forthcoming study on design research. Outside<br />

of design, he has written on aesthetics and art theory photography {Pirelli Work, SteidI, 2006) on the decorative arts; on museums and<br />

their framing of objects and on architecture and architectural theory. He has served on the advisory board of The Journal of Design<br />

History and is now on the advisory boards of the journals Visual Communication, Design Research Quarterly, andThRAD (Portugal).<br />

Gert DUMBAR<br />

'Breakfast, lunch, dinner and disaster pictograms'<br />

Gert Dumbar (1940) studied painting and graphic design at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in The Hague. He studied in the<br />

post graduate graphic design program at the Royal College of Art in London. In 1977 he established Studio Dumbar, where he has<br />

completed numerous extensive corporate identity programs for many major national and international clients including: the Dutch<br />

Postal and Telecom Services {PTT), the ANWB (Dutch Automobile Association), the Dutch Railways, the Dutch Police, the Danish<br />

Post (together with Kontrapunkt a/s, Danmark) and the Czech Telecom. Studio Dumbar won numerous national and international<br />

design awards. Among these were two D&AD golden pencils, a prize that has never been won twice by any other graphis designer<br />

in the world. Since 2003 Dumbar has been teaching at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in The Hague. In addition to this he frequently<br />

lectures at art schools and international design conferences. Between 2000 and 2002 Dumbar was visiting professor at the Royal<br />

College of Art in London. From 1985 until 1987 he was visiting professor there as well and headed the graphic design department.<br />

Since 1980 he has periodically taught and lectured at the University at Bandung, Indonesia. From 1996 until 1998 he was visiting<br />

professor at the Hochschule der Bildenden Künste Saar In Saarbrücken, Germany. From 1998 until 2002 he was a board member at<br />

DeslgnLabor In Bremerhaven, Germany. Dumbar has been the chairman of the Dutch association of Graphic Designers (BNO). In<br />

1987/1988 he was the president of British Designers and Art Directors Association and was a member of the Designboard of the<br />

British Rail Company until 1994. Gert Dumbar is a member of the Alliance Graphlque International (AGI). In 1990 the Humberside<br />

Polytechnic honoured him as Honorary Fellow. In 1994 the Asoclacion de Disenadores Grafaficos de Buenos Aires (ADG) appointed<br />

Dumbar to be a Honourary Member and in 1995 the English Southampton Institute honoured Dumbar with the title of Honourary<br />

Doctor in Design. Dumbar is the initiator of the travelling exhibition'Behind the Seen'about the work of Studio Dumbar, which has<br />

been shown in the Netherlands, Germany, Japan, the USA, China, Australia, Canada and The Hague in 2006.

E n D<br />

"I W A N T D I S O R D E R -- G E T IT?": T H E P A R A D O X I C A L R E P R E S E N T A T I O N S IN<br />

C Q N T E M P D R A R Y A R C H I T E C T U R A L N A R R A T I V E S<br />

Dr.Açalya Allmer<br />

Dokuz Eylül University<br />

Department of Architecture<br />

İzmir, Turkey<br />

acalya.allmer@deu.edu.tr<br />

Abstract:<br />

Underneath outwardly exhibited randomness and disorder<br />

in contemporary architecture today, there is a tendency<br />

towards greater organization for its representation. And this<br />

tension—between order and disorder—provides much of the<br />

narrative power of contemporary architecture. The seemingly<br />

chance encounters of surfaces, materials, or forms - which are<br />

generallyjudged to be negative - are today seen as immensely<br />

exciting. And yet, behind this seemingly disordered outlook,<br />

which demands the attention of the viewer, there is an<br />

enormous organization without which it would be impossible<br />

to build such designs in reality. To demonstrate paradoxical<br />

representations in contemporary architecture this paper turns<br />

toaSimpsonsepisode which features Frank Gehry as the guest<br />

architect who builds a concert hall in Springfield. This paper<br />

argues that playfulness, hollow virtuosity, and mystery are<br />

some of the conditions driving the language of contemporary<br />

architecture - but largely neglected in the current discourse.<br />

Exemplified by the scenes In the episode, the recent work of<br />

Frank O. Gehry will be studied for how it encourages, even<br />

impels, these conditions.<br />

Frank Gehry : ...And none of this would happen if<br />

it weren't for a letter written by a little girl.<br />

Marge Simpson: I wrote that letter.<br />

Frank Gehry : You wrote "You are the bestest<br />

architect in the world"?<br />

Marge Simpson : Well aren't you?<br />

{Simpsons, Season 16, Episode 14)<br />

Figure 1<br />

Underneath outwardly exhibited randomness and disorder in<br />

contemporary architecture today, there is a tendency towards<br />

greater organization for its representation. And this tension—<br />

between order and disorder—provides much of the narrative<br />

power of contemporary architecture. The seemingly chance<br />

encounters of surfaces, materials, orforms-which are generally<br />

judged to be negative - are today seen as Immensely exciting.<br />

And yet, behind this seemingly disordered outlook, which<br />

demands the attention of the viewer, there is an enormous<br />

organization without which it would be impossible to build<br />

such designs in reality.<br />

To accentuate myconcern with the paradoxical representations<br />

in contemporary architecture, I would like to draw attention<br />

to the Simpsons, the most favorite animated family in the<br />

world. In the fourteenth episode of The Simpsons' sixteenth

season (first aired on April 3, 2005 in the US), Frank O. Gehry<br />

is featured as a guest star. As the first architect to appear in a<br />

Simpson's episode, Gehry voiced the part and played himself.<br />

Let me narrate the episode briefly:<br />

TheSimpson family visits the neighbouring town ofShelbyville,<br />

the citizens of Shelbyville call Springfield's residents 'stupid<br />

hicks. 'This makes Marge very angry and when they return,<br />

Marge, as the Chairman of the Springfield Cultural Activities<br />

Board, proposes that the town builds a new concert hall so that<br />

Springfield would be seen as a cultured and refined place. And<br />

to upgrade Springfield's image she suggests Frank Gehry as<br />

the architect of course. We then see Gehry checking his mails<br />

in front of his house in Santa Monica, LA. He receives Marge's<br />

letter, asking him to design a concert hall in Springfield.<br />

Figure 2<br />

Although he is especially impressed by the Snoopy stationary,<br />

hedeniesherrequest, crumples upthe letter and throws it away<br />

on the sidewalk. But when he sees the paper's rumpled shape,<br />

he calls out: "Frank Gehry, you are a genius!" The crumpled<br />

paper transforms into a model for a new $30 million concert<br />

hall and Gehry then presents his design at the Springfield<br />

Town Hall. The town approves and the construction starts.<br />

First we see a regular, orthogonal steel system construction,<br />

and then cranes start swinging wrecking balls to knock and<br />

beat the structure into shape literally. Gehry gives his thumbs-<br />

up once the final form is achieved. However, the opening<br />

night of the Concert Hall was a disaster because apparently<br />

no one in Springfield but Marge likes classic music. And the<br />

building turns into a ruin soon. The town sells the building to<br />

Montgomery Burns who decides to turn it into a state prison.<br />

Figure 3<br />

It might be dubious to pick up the Simpsons to discuss Gehry's<br />

architecture. However, I believe, it can be particularly effective<br />

for illustrating the problems in contemporary architecture in<br />

a comedic narrative. Without argument one can assert that<br />

Gehry's architecture is known worldwide, and he is one of the<br />

few contemporary architects with little interest in theorizing<br />

his work. Needless to say, his work has been controversial. In<br />

many ways, his work speaks for the present problematic state<br />

of architecture and it deserves serious examination.<br />

Gehry in Springfield<br />

Figure 4<br />

Let's start with how Gehry shows up the first time in the<br />

Simpsons episode. At the Cultural Activities Board Marge<br />

mumbles desperately: "Think Marge think. Culture... vulture...<br />

birds of pray... pray In a church... the father, son, and Holy<br />

Ghost... ghosts are scary... scary rhymes with gary... that's it,<br />

architect Frank Gehry!" And she tries to convince the board

members by showing Gehry's Los Angeles Concert Hall seen<br />

on the cover of Concert Hall Weekly where it says: "So Good It's<br />

Gehry!"iVlarge convinces the committee to fund a new concert<br />

hall, designed by Frank Gehry. Sofarİtisstrangelyfamiİiar,asall<br />

the architect audience here would know, Simpsons illustrates<br />

'the Bilbao effect', a phenomenon entered into contemporary<br />

language ofarchitectural discourses afterGehry's Guggenheim<br />

Museum In Bilbao, Spain. The museum changed Bilbao, the<br />

former industrial city in economic decline, into one of the<br />

most popular destinations in Europe; virtually overnight. The<br />

Simpsons episode highlights the municipalities' attempts<br />

to get a Bilbao-esque architectural wonder in their cities to<br />

draw in visitors. Here, the city Is Springfield; the architect is, of<br />

course, Frank Gehry.<br />

Here comes the new concept of'Starchitect'or'Stararchitect',<br />

although giving celebrity status to architects is nothing new<br />

since Renaissance. However, since the popular success of the<br />

Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, the media started to talk<br />

abouttheso-called'Bilbaoeffect'and a star architect designing<br />

a prestige building was thought to be the solution to produce<br />

a landmark for the city. I would like to cut short this discussion<br />

of starchitect, and'Bilbao effect'in an attempt not to reiterate<br />

what is known in current architectural narratives. And yet. It<br />

Is clearly seen that the Simpsons episode offers a relevant<br />

architectural commentary of the last decade, touching on<br />

issues like'starchitect', and'Bilbao effect'.<br />

I am a genius!<br />

Returning to the episode, we see how Frank Gehry gets his<br />

inspiration from a crumpled-up letter on the sidewalk. We<br />

should not forget that it is a highly satirical parody. And yet, it<br />

depicts his empirical design method, which famously begins<br />

at the very low-tech level of crumpled paper models and<br />

assemblages of found objects. Playfulness has been particular<br />

apparent In Gehry's oeuvre since the 70s. The consequences<br />

of this formal playfulness can best be observed, in the<br />

transformation of the architectural design process into a kind<br />

of game. Anthony VIdier (1992, p.102) explained the dilemma<br />

of the notion of play In its resemblance to Alice's playing<br />

croquet with the Queen of Hearts in Alice in Wonderland: 'She<br />

knew what the game was called, but there did not seem to be<br />

any fixed rule and to complicate matters the equipment was<br />

in continuous and random movement. From the flamingo-<br />

mallets to the hedge-hog-balls and the soldier hoops,<br />

everything was open to chance, deprived of the security of the<br />

articulated moves and their known consequences' Similarly, in<br />

Gehry's game, there seems to be no apparent rule. The formal<br />

implications of a design process informed by the aesthetic of<br />

playfulness are also demonstrated in Springfield Concert Hall,<br />

as in other Gehry buildings.<br />

The "bestest" architect in the world!<br />

The impact of technology on architecture Is not new and 1 have<br />

no intention of examining these issues in this paper. What I want<br />

to stress briefly, though, is the duality between construction and<br />

appearance, a crucial theme for today's architectural narratives.<br />

This duality can also been detected In the Simpsons'episode.<br />

Kolorevic {2005, p.n7) asserted that, 'in the new digitally-<br />

driven processes of production, design and construction are no<br />

longer separate realms but are, instead fluidly amalgamated.'<br />

In the episode we see Gehry at the construction site with his<br />

helmet on. Cranes start swinging wrecking balls to knock and<br />

beat the structure into the shape of a typical Gehry building.<br />

He gives his thumbs-up once the final form is achieved. It does<br />

not look like a digitally driven but a crane driven process, design<br />

and construction are done at the same time, amalgamated<br />

in a satirical way. It looks also as if it is very easy to build the<br />

Springfield Concert Hall. And later when the building turns<br />

into ruins, the mayor asks the town, 'Why did you tell that you<br />

did not like classical music?'They reply:'we did not have time,<br />

everything happened so quickly.'This dialog İsa parody of what<br />

happened in the construction of the Concert Hall in Los Angeles,<br />

which took 15 years to finish the construction.<br />

Mr. Burns'budget<br />

Looking at Gehry's architecture, what one sees is the display<br />

of extravaganza, Impetuousness, and technological virtuosity.<br />

But, there is another thing that exists behind the glossy surface,<br />

the unlimited budget of the cWent.lWis raises a number of critical<br />

issues. Perhaps the most obvious of these is that signature<br />

architecture requires rich clients who are able to afford it, such<br />

as Lillian Disney, the widow of Walt Disney, or Paul Allen, the<br />

co-founder of Microsoft, or the Guggenheim family, to mention<br />

only a few. Similarly, rich clients seem to preferGehry's work, as

they are able to represent their wealth through his architecture.<br />

In Walt Disney Concert Hall, for instance, when the 50 million<br />

dollars of Lillian Disney were not enough for completing the<br />

construction, the contribution of the donors saved the life of the<br />

building (Architectural Record, 1995, p.23). The donor names<br />

were etched onto floors and walls in letters proportionate in size<br />

to the amount they gave. The most generous donors had their<br />

names given to the parts of the building: hence, the Eli Broad<br />

auditorium, the Henri Mancini family stairway, and so forth.<br />

The Simpsons episode has a critical commentary on this issue<br />

as well. When the building turns into a ruin, the town sells the<br />

building to Mr. Burns, the fictional character on the Simpsons.<br />

He is the owner of the Springfield Nuclear Power Plant and<br />

Homer Simpson's boss. Mr. Burns is Springfield's richest and<br />

most powerful citizen, with an estimated net worth of $16.8<br />

billion USD (Montgomery Burns, wikipedia). He uses his power<br />

and wealth to routinely do whatever he wants. This time<br />

Mr. Burns has the power to buy the Gehry design-bankrupt<br />

Concert Hall and turn it into a federal prison.<br />

"Ha, ha! No Frank Gehry-designed prison can hold me!"<br />

Simpsons offer the biggest tragedy that has happened in<br />

a Gehry building: 30 million dollar Springfield Concert Hall<br />

ends up being converted Into a prison. Here we see another<br />

paradox. With a little effort, a concert hall can be turned into<br />

a prison. Is it not a known fact that Gehry's projects are all<br />

extremely similar in their sculptural language of curvilinear<br />

forms? From the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao to the Walt<br />

Disney Concert Hall, the EMP, the Richard B. Fisher Center for<br />

Performing Arts at Bard College and the Ray and Maria Strata<br />

Center at MIT, they are generally undifferentiated given the<br />

program, cultural context or existing site context.<br />

There Is no Intention to discuss Gehry's complete work In this<br />

paper. Instead it is intended to focus on some of the conditions<br />

driving the language of contemporary architecture. Gehry's<br />

architecture finds its realization in its exploitation of the<br />

latest technological advances. No argument can be made<br />

against this. He takes pleasure In displaying the technological<br />

capabilities of contemporary architecture thus leaving the<br />

spectator in a state of wonder at the skill and technical mastery<br />

that lies behind its construction.<br />

Figure 5<br />

Here I want to Introduce the idea of virtuosity for its own sake<br />

as another theme important for Gehry's recent architecture.<br />

What seems to be neglected in the contemporary discussions<br />

of architecture, however, is that a certain display of technical<br />

virtuosity - virtuosity for its own sake - is taken for granted, it Is<br />

apparent that a certain principle of technological virtuosity is<br />

essential to the realization of Gehry's architecture. This pursuit<br />

of virtuosity for its own sake culminates In Gehry's architecture<br />

with an Intention to leave the spectator in a state of wonder at<br />

the skill and technical mastery that lies behind its construction.<br />

Gehry depends on playful virtuosity to send the visitor out of<br />

the building grinning with delight.<br />

Figure 6<br />

"Frank Gehry, you like curvilinear forms much?"<br />

Speaking of rich clients, 1 want to give another building as<br />

example: the Experience Music Project (EMP) in Seattle,<br />

Washington (1995-2000), the ideal building for Gehry to test<br />

his ideas. A representative of the triumph of technology,

Microsoft cofounder Paul Allen acted as client with deep<br />

pockets for the EMP project. The private funding for this<br />

publicly accessible project meant the citizens of Seattle had<br />

no authority to be involved or influence on the design of the<br />

EMP {unlike Springfielders). Gehry's freedom is evident when<br />

looking at the plan of the EMR Lacking any of the traditional<br />

Gehry back of house budget-meeting boxes to which forms<br />

are draped; the EMP plan appears organic in nature. With the<br />

exception of "Sky Church", the remaining five programmatic<br />

volumes have seemingly chance encounters of surfaces,<br />

materials, or forms.<br />

Figure 7<br />

Behind this seemingly disordered outlook, there is an<br />

enormous organization without which it would be impossible<br />

to build such designs in reality. Gehry adopted a number of<br />

various advanced technologies to facilitate the construction<br />

of the EMR The most important tool being the CATIA<br />

(Computer Aided Three-dimensional Interactive Application}<br />

software used to model the building three-dimensionally. As<br />

an adaptation from aerospace Industry, this software has the<br />

ability to flatten complex multiple-curved surfaces which can<br />

then be used as a template to cut them into pieces. At EMP<br />

the flattened shapes of exterior panel cladding were cut using<br />

CAD/CAM and CNC (Computer Aided Drafting/Computer<br />

Aided Manufacturing, Computer Numerically Controlled)<br />

milling machines one by one and bending them back into<br />

their shape before mounting them in place on the building<br />

using GPS location devices and a highly customized mounting<br />

system which allows for adjustment (Linn, 2000, p. 175). One<br />

peculiar aspect in this construction process needs to be<br />

mentioned is the employment of custom-made elements,<br />

which represents an important change in the logic of building<br />

production. The use of custom-made pieces is one of the<br />

elements that makes Gehry's architecture unique, but at the<br />

same time makes it troubling. No two panels are similar out of<br />

the roughly four thousand panels covering the EMP exterior.<br />

Although the process of creating templates and cutting the<br />

shapes was highly automated by way of CATIA, these complex<br />

shapes had to be hand bent into their final shape and hand-<br />

assembled to include the necessary structural supportive<br />

metal fin framing. Each panel holds about seven shingles each<br />

of which has a unique shape and size. Each shingle is tailored<br />

to fit exactly in its designed location and each panel Is woven<br />

together in situ. As a result, the building's surface looks like a<br />

patchwork fabric.<br />

The notion of patchwork fabric, 1 have just Introduced, can be<br />

further studied considering a specific set of buildings. From the<br />

EMP, to the Jay Pritzker Pavilion In Millennium Park In Chicago<br />

(2004) (here 1 can add Springfield Concert Hall projecttoo), there<br />

is an apparent change in the surface treatment. The enveloping<br />

surface wrapping around the building, as in Bilbao, became<br />

continually {but unexpectedly) interrupted or broken in Gehry's<br />

later projects such as the Millennium Park pavilion. This frayed<br />

characteristic of the building's surface reveals the thinness of<br />

the surface, thus exposing the artificiality of his gesture.<br />

Figure 8<br />

The consequence of this series of interruptions on the<br />

metal surface is "the frayed and torn drapery," demanding<br />

the attention of the viewer and aspiring to the status of<br />

an autonomous sculptural object. Here, I would like to<br />

draw attention to the pattern of the draped surface. As

Leatherbarrow and Mostafavi (2002, p.l98) asserted, 'the<br />

patchwork of panels that makes up its surface is composed<br />

of pieces that have been cut from the same cloth, giving the<br />

building's novel geometries great regularity and cohesion.'<br />

This is evident in almost all of the buildings built after the<br />

EMP. Despite of their apparent formlessness, the pattern of<br />

their cladding appears to be cohesive and repetitive. Given<br />

the materiality and weight of the building, rendering such a<br />

surface is not an easy task. Nonetheless, it becomes a vehicle<br />

for displaying technological virtuosity, spectacle, and mystery,<br />

through which Gehry earns his appearance in the Simpsons.<br />

Figure 9<br />

REFERENCES:<br />

'The Seven-Beer Snitch', the fourteenth episode of The<br />

Simpsons' sixteenth season, 2005, television program. The<br />

FOX Network, US, 3 April.<br />

Kolorevic, B 2005,'Designing and Manufacturing Architecture<br />

in the Digital Age', Architectural Information Management,<br />

no. 3, p. 117.<br />

II •<br />

Leatherbarrow, D & Mostafavi, M 2002, Surface Architecture,<br />

The MIT Press, Cambridge.<br />

Linn, C 2000, 'Creating Sleek Metal Skins for Buildings^<br />

Architectural Record, vol.188, no.10, pp. 178. ^ ^<br />

'Frank Gehry's Walt Disney Concert Hall -his Masterpiece-<br />

Dances with Death' 1995, Architectural Record, vol. 183, no.<br />

10, p. 23.<br />

'Montgomery Burns', wikipedia, viewed 20 December 2005,<br />

<br />

Vidler, A 1992, The Architectural Uncanny: Essays in the<br />

Modern Unhomely, The MIT Press, Cambridge.<br />

1

O N T H E R E L E V A N C E D F B LI N D-VARI ATI a N-AN D-S E L E C T I V E - R E T E NTI D N İN<br />

C R E A T I V E A R C H I T E C T U R A L P R O B L E M S D L V I N B W I T H I N T H E C O N T E X T O F<br />

A R C H I T E C T U R A L E D U C A T I O N<br />

Hakan Anay<br />

Middle East Technical University,<br />

Department of Architecture, Ankara, Türkiye<br />

hakananay@yahoo.com, anay@metu.edu.tr<br />

Abstract<br />

Blind-variation-and-selective-retention process is essential<br />

for ail genuine gains and achievements in epistemic activities<br />

such as thinking, learning, and general problem solving. This<br />

idea is fundamental to the conception of "creativity" and<br />

"creative thought" in "evolutionary epistemology,"and should<br />

be equally applicable to the epistemic activities concerning<br />

"creativity" and "creative thought" such as architectural<br />

problem solving. Taking this argument as its basis, the present<br />

study examines and discusses the relevancy and applicability<br />

of blind-varlation-and-selective-retention as a model for<br />

architectural problem solving, particularlywithin the context of<br />

architectural education, it underlines particular characteristics<br />

of the model that should be considered prior to its adoption<br />

to architecture which these characteristics also point to lines<br />

of research which should be considered in depth.<br />

The present paper is based on the idea that bllnd-variation-<br />

and-selective-retention process Is essential for all genuine<br />

gains or achievements in epistemic activities such as thinking,<br />

learning, and general problem solving. (See Campbell 1960)<br />

This idea Isfundamentaltotheconceptlon of'creatlvethought"<br />

in "evolutionary epistemology," particularly in the works of Karl<br />

Popper and Donald Campbell and should beequallyappllcable<br />

to the epistemic activities concerning "creatlvlty"and "creative<br />

thought"such as architectural problem solving.' The main aim<br />

of the present study is to examine and discuss the relevancy<br />

of blind-variation-and-selective-retention process as a modeP<br />

for creative architectural problem solving within the context<br />

of architectural education. Its main thesis is that we can<br />

expand this model for the (re)conception of problem solving<br />

and "creative thought" or "creativity" in architecture, with<br />

some reconsiderations and modifications. Consequently the<br />

model will be profitable for architectural design education, for<br />

teaching/learning how to design and for gaining architectural<br />

knowledge.<br />

The nature of blind-variatlon-and-selective-retention<br />

process<br />

Blind-variation-and-selective-retention process in problem<br />

solving Is fundamentally based on trial-and-error with an<br />

"evolutlonary"argument.The process has following essentials<br />

(See Campbell 1960,1974):<br />

' The present paper is based on the hypothesis that architectural<br />

design can be evaluated as a "type of" problem solving activity in the<br />

sense that it is a purpose driven or teîeological process where acts<br />

of making, evaluation and remaking take place towards the creation<br />

of a work that potentially fulfils the objectives, or provide a solution<br />

to the stated architectural problem. The activity has an "epistemic"<br />

nature since it concerns and requires utilization and production of<br />

various levels and types of knowledge. However this does not amount<br />

to architectural design equals to problem solving or reduction of<br />

architectural design to a mere knowledge activity. These uses are for<br />

convenience, for isolation and foregrounding certain aspects of a very<br />

complex activity such as design that helps the paper to clarify the<br />

main problem, set its main argument and discuss the relevancy of it.<br />

^ The use of the term "model" refers to "a simplified description of a<br />

complex entity."

1."a mechanism for introducing variation," namely a series<br />

of -blind- trials which attempt to make a forward move<br />

which potentially carry the process from one stage to<br />

another, towards the solution.<br />

2. a "consistent" intentional "selection process" which<br />

eliminates the unsuccessful trials while keeping the<br />

successful ones.<br />

3. "a mechanism" for preserving the successful-so-far<br />

variations, and a "mechanism"for transferring them to the<br />

next series of trials.<br />

The process has an evolutionary argument in the following<br />

accounts: trials are more or less accidental or blind gambits,<br />

varied from the previous successful-so-far moves. Each gambit<br />

is controlled by a selection mechanism, which eliminates<br />

erroneous or unsuccessful moves, while leaving the successful<br />

ones to continue the search process.<br />

Blind-variation-and-selective-retention process in<br />

architectural problem solving<br />

The architectural adaptation of the model is based on<br />

the following main assumptions: In architectural problem<br />

solving, like all other problem solving processes, a blind-<br />

variation-and-selective-retentlon process is fundamental to<br />

all "genuine" and "creative" achievements. This intrinsically<br />

implies that in creative architectural problem solving, making<br />

always comes before selection and modification. Any shortcut<br />

bypassing this process, such as adoption of an Initial solutlon-<br />

in-prlnciple, schemas, or use of patterns, is dependent upon<br />

already existing knowledge or wisdom gained earlier by blind-<br />

variation-and-selective-retention -in a great extent- from<br />

earlier solutions. This viewpoint also implies that architectural<br />

problem solving activity Is actually embedded in the world of<br />

architectural works and architectural problems. In this sense,<br />

these arguments also apply to adaptation of earlier knowledge<br />

or wisdom to the new conditions which -also- requires more<br />

or less blind-variation-and-selective-retentîon process.^<br />

However, at first sight, blind-variation-and-selective-<br />

retention model ofarchitectural problem solving seems to be<br />

contrasting with the conventional view(s) of problem solving<br />

In two accounts. Dwelling on these widely accepted Issues<br />

may help us to clarify the model and adopt it to architecture.<br />

First, it is often argued that some sort of already achieved<br />

knowledge and wisdom reduces thefrequency of blind search,<br />

or trial-and-error Is not random or blind at all (See Campbell<br />

1960, Simon 1969, Akin 1986, Newell et'al 1958). For example<br />

in the Sciences of the Artificial, Herbert Simon (1969) argues<br />

that existence of previous knowledge or experience gained<br />

from "similar" or earlier problems affects the frequency of<br />

"trial and error" in the problem solving activity to the degree<br />

that it can be "altogether eliminated." Similarly, Newell et' a!<br />

(1958) argue that "trial-and-error attempts take place in some<br />

'space'of possible solutlons."Trials are controlled by some type<br />

of strategy that makes the progress "meaningful." A strategy<br />

"either permits the search to be limited to a smaller sub-space,<br />

or generates elements of the space in an order that makes<br />

probable the discovery of one of the solutions early in the<br />

process." (Newell et al. 1958) It is true that previous knowledge<br />

and wisdom provides a basis to begin with and proceed,<br />

and it provides shortcuts in creative search İn various stages<br />

and levels. In fact this is required, since no problem solving<br />

starts from a tabula rasa. But "knowledge" cannot altogether<br />

eliminate the "blind" search since what is creative and new<br />

Is what is -yet- unknown to us. If we reformulate, "creativity"<br />

means going beyond what was already known and achieved,<br />

therefore It should be blind. Knowledge of earlier solutions is<br />

essential to architectural problem solving, but even the use of<br />

earlier forms for the conception of new ones is not about basic<br />

repetition or imitation but requires interpretative/creative<br />

modification prior to their application to new conditions<br />

^ Architectural problem solving activity can be evaluated as<br />

"evolutionary" and "epistemîc" in two accounts: first, the activity is<br />

evolutionary since each work is somehow tied to tradition, earlier<br />

solutions, problems, and earlier body of knowledge. However, this<br />

type of "evolutionary" continuity is relatively more open to shifts,<br />

ruptures and discontinuities, and the "evolutionary" link might no be<br />

clear and observable at all. Second, the problem solving "process"<br />

itself is "evolutionary" since every new stage is successor of earlier<br />

stages and a modified or transformed version of them. This type of<br />

"evolutionary" continuity is generally not concern shifts and ruptures,<br />

and the "evolutionary" line is more clear or observable.

which also requires a type of blind-variation-and-selective-<br />

retention process.<br />

Simon (1969) further argues that problem solving activity<br />

"involves much trial and error" and "the more difficult and<br />

novel the problem, the greater is likely to be the amount<br />

of trial and error required to find a solution." However, "at<br />

the same time, the trial and error is not completely random<br />

or blind; as it was in biological evolution, but "...it is in fact,<br />

rather highly selective." (Simon 1969) He states that "the new<br />

expressions that are obtained by transforming given ones are<br />

examined to see whether they represent progress toward the<br />

goal. Indications of progress spur further search In the same<br />

direction; lack of progress signals the abandonment of a line<br />

of search." (Simon 1969) This might mean even if we do not<br />

possess any prior knowledge or experience related with the<br />

current problem situation, we can still determine the course of<br />

our search tovyards a goal: "problem solving requires selective<br />

trial and error." (Simon 1969) However, drawing a "search"<br />

direction Is also a trial, and precedes our evaluation of whether<br />

the line was progressive or not if it was not based on an earlier<br />

wisdom of some type. In addition, a currently progressive line<br />

does not guarantee that that it will remain so, or it will yield<br />

a successful solution, respectively a currently regressive line<br />

may turn into a progressive one if pursued further, and may<br />

lead to a successful solution. It is obvious that architectural<br />

problem solving Is not a random but a goal driven, intentional<br />

activity. Sut the source of intentionallty does not lie in the<br />

"making;' or in the "trials," but in the "selection" process. In<br />

other words, in architectural problem solving, goals are not<br />

totally attained through foreslghtful moves, but also by blind<br />

"trials," and the selection of unsuccessful trials followed by<br />

bearing on to explore the best-so-far trial lines. So we may<br />

reformulate the argument as follows; creative problem solving<br />

requires knowledge of earlier solutions and wisdom to start<br />

with and proceed, but at the same time it involves a blind trial,<br />

and selective error elimination, or more specifically, bllnd-<br />

variation-and-selective-retention process.<br />

Second account that seems to be conflicting with the idea of<br />

blind-variation-and-selective-retention is that architectural<br />

problem solving is purpose-oriented and teîeological.'' The<br />

main purpose of the architectural problem solving activity Is<br />

to construct a work that will -potentially- provide a solution<br />

to the formulated problem.Typicaliy, an architectural problem<br />

is stated in the form of a brief or a program. A popular view<br />

of architectural design, which was perhaps descendant from<br />

the functionalist doctrine in architecture, proposes that the<br />

program is the only legitimate and neutral source and origin<br />

of the form, an asset which directly implies, governs the<br />

formalization process and the solution: Form or the solution<br />

is something postulated as the purpose or posited at the<br />

expense of function or program. This view of architectural<br />

problem solving is problematic at least In two accounts: first,<br />

the program can neither be objective nor comprehensive.<br />

There will always be preconceptions and prejudices playing<br />

an active role In the preparation of a program, and for this<br />

reason, the program will always be selective and biased. (See<br />

Rowe 1996) Second, even If such a program exists, there is no<br />

algorithm, and no method that can guarantee a program to<br />

be directly translated into a meaningful form or solution. This<br />

problem was perhaps best stated by John Summerson (1957)<br />

as follows: "The conceptions which arise from a preoccupation<br />

with the programme have got, at some point, to crystallize<br />

into a final form and by the time the architect reaches that<br />

point he has to bring to his conception a weight of judgment,<br />

a sense of authority and conviction which clinches the whole<br />

design, causes the impending relationships to close into a<br />

visually comprehensible whole." But he confesses that there<br />

We may distinguish at least two main types of teîeological<br />

achievements which an architectural problem solving activity<br />

might concern: first is intrinsic to the activity or the process itself<br />

and actually embedded in it. It concerns construction or design of<br />

an architectural work that should provide a -potential- solution to<br />

an architectural problem which was stated in the program or the<br />

brief. In this sense "prog ram"or purpose is an element which actively<br />

plays a constructive or formative role in the process. Second resides<br />

beyond the process and the work. It concerns for example an<br />

intended change in the environment through architecture; better<br />

living conditions, a livable city, more accessible environment and<br />

buildings, etc. In this case, the control between the work and the<br />

intended modification or change is not direct and clear. The model<br />

proposed here particularly concerns the first category. However, an<br />

architectural work can still be considered as a "device" that has the<br />

potential and responsibility to make a change in the environment,<br />

which can be interpreted as a "trial."

is a "hiatus:""tinere is no common theoretical agreement as to<br />

whathappensorshould happen at that poinf'of crystallization.<br />

(Summerson 1957) It is true that program is a fundamental<br />

"constructive" or "formalizing" element in architectural<br />

problem solving, but the problem is that it is often misplaced<br />

in its widely accepted concept!on(s). Program or purpose<br />

neither implies the solution nor prescribes the formalization<br />

of the solution, but only good for selection and judgment: Any<br />

teleologica! achievement in architectural problem solving is<br />

notattained-fully-through direct formalization process, based<br />

on the program, plan, aim, purpose or something else similar,<br />

but through blind-variation-and-selective-retention, or more<br />

architecturally, through making, selection by criticism, and<br />

remaking. Program or aim is not good for directly "forming"<br />

the solution but only for "selection" and through the selection<br />

process for guiding the course of "search" and consequently<br />

determining the"so!ution."<br />

In a final analysis, conventional views of problem solving are<br />

compatible with blind-variation-and-selective-retention in<br />

these two seemingly-contradicting accounts. They rather seem<br />

to focus and foreground certain aspects of creative problem<br />

solving which are already contained by the proposed model.<br />

To sum up and reformulate, architectural adaptation of the<br />

proposed model has three essential points:<br />

First, creative problem solving in architecture, as in other<br />

problem solving processes, requires knowledge of earlier<br />

solutions and wisdom to start with and proceed, but at<br />

the same time it involves a blind trial, and selective error<br />

elimination, or more specifically, blind-variation-and-selective-<br />

retention process. We may adopt this process to architecture<br />

as follows: creative problem solving in architecture calls for a<br />

process of making, critical selection (or selection by criticism),<br />

and remaking.<br />

Second, knowledge of eariier solutions is essential in<br />

architectural problem solving, but the use of eariier forms<br />

for the conception of new ones is not about basic repetition<br />

or imitation but requires an in depth understanding and<br />

interpretative/creative transformationpriortotheirapplication<br />

to new conditions which also requires a blind-variation-and-<br />

selective-retention process. Since the solution already exists.<br />

the process of understanding can be interpreted as more of a<br />

hypothetical (re)construction.<br />

Third, any teleological or purpose-oriented achievement in<br />

architectural problem solving is not attained -fully- through<br />

direct formalization process which is prescribed in the purpose,<br />

program or problem formulation, but through making and<br />

selection by criticism, or by blind-variaîion-and-seiective-<br />

retention process.<br />

Conclusion: Things to (re)consider<br />

If blind-variation-and-selective-retention model will be<br />

adopted and employed for architectural problem solving,<br />

particularly within the context of architectural education,<br />

various essentials must be (re)considered. These essentials<br />

also point to various research lines or fields that should be<br />

studied in detail.<br />

1. There must be methods and strategies and also tools<br />

for the analysis and understanding of the existing works<br />

of architecture for gaining already existing knowledge<br />

and wisdom as the basis for creative investigation. In<br />

architectural problem solving, reliance on tradition Is<br />

inevitable: one must start where his or her predecessors<br />

left. This has the primary importance for the students<br />

of architecture since they barely possess the required<br />

background knowledge to start with, and proceed the<br />

search process.<br />

2. Variation-creation is essential to the proposed model.<br />

However, creation of many variations or parallel exploration<br />

lines seems to be contradicting the conventional making<br />

habits of architectural problem solving. Still it seems to<br />

be a viable approach particularly for education, but needs<br />

further investigation.<br />

3. Combined with the previous, there is also a need for<br />

methods and strategies and also tools for making and<br />

variation-creation process. Existence of methods and<br />

strategies-although they still do not guarantee the success-<br />

Is what makes the difference between "blind" search and<br />

"random" search. Tools help methods and strategies work<br />

or even make them available to this process.

4. Creation of many variations or parallel exploration<br />

lines seems to be harder and more complex than the<br />

conventional making habits seeming o follow a single<br />

line. It seems that computer software is a viable and<br />

powerful tool to be used for this purpose if they were once<br />

(re}considered and (re}designed particularly to support<br />

this process.They can further provide seamless control on<br />

the"evolutionary" process. (See Anay 2005)<br />

5. There is a need for experimentation and free play: the<br />

point is; an unblocked forward movement is essential for<br />

"creativity.'This must not be confused with "free expression,"<br />

or a similar unmedlated making activity. Any forward<br />

movement should depart from the existing wisdom, or<br />

should be based on the criticism of what already existed,<br />

and should be controlled by rigorous selection through<br />

criticism.<br />

6. Combined with the previous, there Is a need for rigorous<br />

selection processes. In architecture this is generally tied to<br />

problem formulation, program and contextual forces. It is<br />

worth to restate that neither of these or similar assets imply<br />

or prescribe the solution. Critical selection (and retention)<br />

is the only way for reaching teîeological achievements in<br />

architectural problem solving.<br />

7. There Is a need for methods, mechanisms and tools<br />

enabling the continuity of the evolutionary process, for<br />

preserving the successful-so-far solutions, and Informing<br />

the next generation of variations. It must be noted that<br />

this is relevant for both within the unique problem solving<br />

process; from one stage to another, or without it; between<br />

the present architectural problem solving process and the<br />

problems and the solutions preceding it.<br />

Finally, It must be underlined that previous arguments also<br />

(re)locate the tradition (or the body of earlier knowledge)<br />

and the program (or architecture's Utopian or teîeological<br />

component) within the architectural problem solving process.<br />

This structure differs from most "accepted" approaches,<br />

but essential, and must be considered as such prior to Its<br />

application In any area Including education.<br />

References<br />

AKIN, Ö., 1986, Psychology of Architectural Design, London:<br />

Pion Limited<br />

ANAY, H., 2005, Towards a Reconsideration of Computer<br />

Modeling in the Idea-Creation and Development Stages of<br />

the Architectural Design Process In: New Design Paradigms,<br />

Conference proceedings of lASDR 2005 Taipei-Taiwan<br />

CAMPBELL, D.T., 1960, Blind Variation and Selective Retention<br />

in Creative Thought as in Other Knowledge Process, In:<br />

Psychological Review, Vol. 67, No. 6,380-400.<br />

CAMPBELL, D.T., 1974, Evolutionary Epistemology, In: P.A.<br />

Schtipp (Ed.) The Philosophy of Karl Popper, La Salle, Illinois:<br />

Open Court, 413-463.<br />

NEWELL, et'al., 1958, Elements of a Theory of Human Problem<br />

Solving, In: Psychological Review Vol.65, No. 3,151-166.<br />

POPPER, K.R., 1972, Objective Knowledge: An Evolutionary<br />

Approach, Oxford: At the Clarendon Press<br />

ROWE, C.,1996, Program versus Paradigm: Otherwise Casual<br />

Notes on the Pragmatic, the Typical, and the Possible In:<br />

A.Caragonne (Ed.) As 1 was Saying: Cornelliana,The MIT Press<br />

SIMON, H., 1969, The Sciences of the Artificlal,Cambrldge,<br />

London, Mass.: The M.l.T. Press<br />

SUMMERSON, J., 1957, The Case for a Theory of Modern<br />

Architecture, In: R.I.B.A. Journal

G D M P U T E R A I D E D D E S I G N (GAD) A N D C D M P U T E R A I D E D M A N U F A C T U R I N G<br />

(GAM) IN T H E J E W E L L E R Y S E C T O R IN T U R K E Y<br />

Dilek Ayyildiz<br />

Industrial Product Designer<br />

Research Assistant<br />

Doğuş University, Faculty of Fine Arts and Design,<br />

Industrial Product Design Department<br />

Istanbul, Turkey<br />

dilekayyildiz@gmail.com<br />

Abstract<br />

The jewellery sector in Turkey, which is the second most jewel<br />

exporting country in the world after Italy, gained dynamism<br />

by the use of computer aided design (CAD) programs. While<br />

previously the molds and the models were made in a small<br />

quantity by the craftsmen In the workshops around Grand<br />

Bazaar, now more designers have begun to work in this sector<br />

by using CAD programs such as Jewelcad, Rhino and Matrix.<br />

Now designers not only design the models and leave the<br />

production process to the craftsmen, they also draw the mold<br />

designs by using CAD programs.<br />

Jewellery sector has become a more innovative one by CAD<br />

and computer aided manufacturing (CAM) systems. Especially<br />

by designing much more models and molds, production gained<br />

a huge speed and the decrease in costs caused an increase<br />

in exportation. Besides, designs that have perfect finishes are<br />

produced by using CAD programs and CAM systems.<br />

This paper includes the process of jewel production by using<br />

CAD and the stages of CAM. Also there will be some examples<br />