Although she was born in the year of the Soviet revolution and her final claim to fame was longevity, Zsa Zsa Gabor, who has died at 99, was in many ways an oddly modern figure.

The concept of being “famous for being famous” and creating a personal brand around a way of dressing or speaking – which has become a common career path through reality TV and social media – was pioneered by the Hungarian-American seven decades ago.

Strikingly, the reminder tagline usually applied to people in obituaries – screen star, author, broadcaster – is problematic in her case. Her movie credits include decent contributions to two classics – John Huston’s Moulin Rouge (1952) and Orson Welles’s Touch of Evil (1958) – and her published works range from a co-authored novel to dating-and-mating handbooks such as How to Catch a Man, How to Keep a Man, How to Get Rid of a Man.

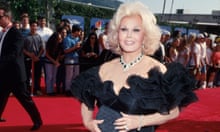

However, she spent much of her career as a star and talkshow guest with an aura that was drawn from no particular achievement. While other guests on television shows were generally plugging books or films, Gabor was most often just promoting herself. She constructed around herself an image of glamour and exoticism that depended on giving off a scent of money, cigarettes, sex, Riviera holidays and caustically drawled remarks – the recipient of which was often addressed as “dahlink”.

Being a multiple divorcee was a key part of her persona: she belonged with Henry VIII, Elizabeth Taylor and Joan Collins in the small group of those known for making the wedding ring a disposable item. Curiously, Gabor and Taylor both married into the same American hotel empire (marrying Conrad Hilton Sr and Jr respectively). In a UK context, Gabor’s nearest equivalent is probably Collins, who has also become more celebrated for ageing well and living stylishly than for any specific form of work. But Collins (on five marriages) – and even Taylor’s seven and Henry’s six – look almost monogamous in comparison with the nine spouses accumulated by Gabor.

Many of the one-liners for which she became known relate to this matrimonial industry. “I am a marvellous housekeeper. Every time I leave a man I keep his house,” she said. When people unable to keep up would check with her how many husbands she had had, she would say: “You mean just my own? Or other women’s as well?”

Tough to be the husband of, she was also not easy in professional encounters, and became known for extreme prima donna behaviour. Gabor was once removed by security officers from a Delta airlines flight for refusing to keep her retinue of six dogs in their travel kennels. On another occasion she slapped the face of a police officer who stopped her for a driving violation. She reportedly objected to wheelchair users sitting close to stages on which she performed. Gabor features in several anecdotes told on the talkshow circuit about nightmare guests, being accused of hard demands and an imperious manner. In public and private, she was the grandest of dames.

In becoming known for having a pithy quote for everything, she anticipated Twitter, but her greatest cultural precocity was an early appreciation of how lucrative self-promotion could be. It was no coincidence that in both her first movie, Lovely to Look At (1952), and her last, A Very Brady Sequel (1996), the character she played was called Zsa Zsa Gabor. This merging of part and player occurred in many of her other films as well. The first impact she made on America – in her early-20s – was through the serialisation of a fiction based on her early life. She always knew that she was the story.

A crucial part of that narrative was her European roots and allure. Most showbiz agents in the 1940s, if seeking a US career for a Hungarian war refugee called Zsa Zsa Gabor, might have kept the surname (with its useful echo of Garbo, already a star) but changed her first name to Zelda, and dispatched her to voice school to lose those Budapest vowels. But, whether from stubbornness or a precocious understanding of celebrity, Gabor kept both the name and the way she talked. It proved to be a shrewd move. Even if interviewers and fans were sometimes unsure how to pronounce Zsa Zsa, the doubled purring sound helped to create an exotic and sensual mystique.

Her Hungarian background always worked to her advantage. The American republic has often reacted to the British monarchy and aristocracy it spurned at birth, and intermittently tried to create a replacement via means including movie stardom, Ivy League education and Wall Street.

Gabor was a personal experiment in becoming an American princess, combining Mitteleuropa breeding with Hollywood glamour in a way that enchanted gossip columnists and TV producers. If many people were unsure quite what she did, they knew, across seven decades, exactly who she was. Which, for Zsa Zsa Gabor, was a definition of success.