Scissors, paper, pins – these were all it took for Matisse, in the last years of his life, often bedridden and feeling he was living on borrowed time, to create the works that now fill a suite of galleries at Tate Modern. What a joyous and fascinating exhibition this is. I eat it with my eyes and never feel sated.

Ravishing, filled with light and decoration, exuberance and a kind of violence, Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs is about more than just pleasure. It charts not simply the consummation of the artist's long career but a kind of self-usurpation. In his last years, Matisse went beyond himself.

As well as the works themselves, there is film footage of the artist and his assistants at work, swatches of the hand-painted papers he used, and a wealth of photographic and other material to broaden our understanding.

And at the heart of the show is Matisse's sinuous cutting and slicing, not just of paper but of space itself – the scissor-sharp separation and cleaving of colour and blankness, depth and flatness, punch and retreat; energy held in check and then released. Matisse created a universe that filled the room around him, spilling from the walls to the floor. "Space has the boundaries of my imagination," he said.

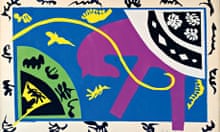

Colour dances, and our eyes dance with it, following contours and edges, sliding from shape to shape, wallowing in a whiteness that becomes electric, jumping from positive to negative and back again. There is no stasis, no arrest, but a constant discovery of newness at every turn: a swallow swerves in flight, a shark swims the wall. Pinned to his chest, Icarus's heart explodes. Foliage proliferates and bees swarm. A mermaid appears, where a thoughtful blue nude once sat, watched by a parakeet.

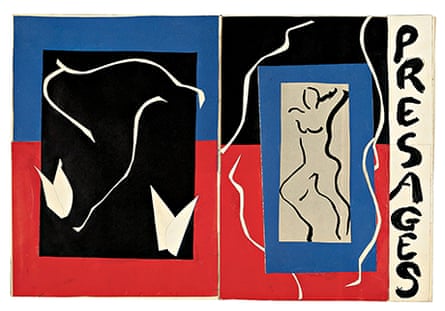

The exhibition takes us from the late 1930s to the artist's death in 1954, from his use of cut-out slips of paper as aide-memoires and tools in the composition of his paintings and try-outs for projects, to the cut-paper collages he made for books. An entire room is devoted to his book Jazz and the collages he made for it. A great deal of space is given over to his preparatory material for the chapel at Vence. But we keep coming back to a single room, both studio and bedchamber and the place where he slept and dreamed and suffered from cancer and other miseries and where, when he awoke, he found himself in the midst of his work.

Seeing the cut-outs now – intense, expansive, open, complex and complicated for the eye to travel and to apprehend – is not to see them as Matisse made them in this bedroom-cum-studio. There, all the elements – pinned to the wall, piling up on desks and tables and, doubtless, the floor – were suspended in flux. The papers curled and drooped from the wall and trembled in the draughts, and changed as light and shadows shifted round the room.

It is a very different matter to overpaint, scrub out and adjust a painting than it is to take down and re-pin a shape on the wall. The cut-out forms seem effortless. Their arrival has no history. Mobile, unfixed, unbounded, they have a stunning immediacy.

I imagine the sound as the big scissors (perhaps intended for dress-making, or for the paper-hanger's trade) carved through paper already stiffened by the gouache paint that had been applied to it. And Matisse directing his assistants as they first supported and helped him rotate the sheets as he cut the big shapes, then, under his direction, positioned them on the wall, hammering them on to the plaster with panel pins. You imagine Matisse in his dressing gown giving directions from his wheelchair, a carved snowfall of colour on the floor about him.

The great thing was that the work was unending. That permanence came so late into the process. Sometimes a very large cut-out could be done in a couple of days. At other times the shapes were placed and replaced many times.

There is a kind of flight in Matisse's cut-outs. Flight from his infirmity and increasing physical limitations, flight not just from his own impending death and also from the suffering of his daughter, Marguerite – horribly tortured by the Gestapo in the last year of the war for her part in the Resistance.

More than painting or sculpting by other means, the cut-outs are also more than decoration, even though the decorative spirit gives them such a sense of liveliness. Matisse admitted that he began making the cut-outs and pinning shapes to the wall without much idea where it was leading, though the essence of the technique had been with him for decades. These earlier works were always bounded by the limits of a canvas or a page, or the proportions of a wall or a recess (Matisse remarked that he would become a fresco painter after he died).

The late cut-outs had no such boundaries. Photographs and films shot at the time show us how shapes reached to the ceiling, slid behind the radiator in the corner and spilled from one wall on to the next. They began to encroach on to the floor. Their forms sometimes migrated from one work to another. A single shape could exist on its own or in concert with others. And it all happened in that room.

The catalogue would like us to think that what Matisse was doing was akin to installation, and also to the kind of studio-centred art made by Bruce Nauman. Nauman's work is often borne out of a sort of creative emptiness, studio activity – and inactivity – becoming its focus. Matisse's paintings, throughout his career, frequently depicted the room where he worked. He never lets you forget the artifice not only of painting itself, but also the material circumstances in which it is made. People sometimes laugh about artists who go on about closing the gap between art and life, but Matisse – and Picasso – thrived on the tensions and the hinterlands between the two.

Looking at the cut-outs now, we are apt to forget how they looked before the positions of his shapes were finally mapped and traced, and before these floating, fragile forms were fixed and flattened to large paper sheets that were then laid down on canvas, and contained once again by a rectangle and a frame. Even at the time, it was suggested to Matisse that he mount the cut-outs in deep box-frames, and fix the shapes with pins rather than have them flattened. For all sorts of technical and doubtless financial reasons, this never happened.

Yet Matisse had a prescient awareness of the implications of what he was doing. "It seems to me I am anticipating things to come," he said. "It will only be much later that people will realise to what extent the work I am doing today is in step with the future." He also foresaw a possible end to painting. It didn't happen, but the potential of the cut-outs has already been unleashed. How rich all this is, how marvellous, how alive.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion