Henri Michaux, the Belgian-born writer and artist, arrived in Paris in 1924, the same year that André Breton published the First Surrealist Manifesto. Michaux is often mischaracterized as a “Surrealist”; he dabbled a little in the inescapable clan of writers and artists, and certainly shares their concerns about the failures of language and divisions of the self. In the newly translated Thousand Times Broken, a slender volume of poetry, prose, and black and white images (exquisitely translated into captivating, strange English by the poet Gillian Conoley), Michaux continues to explore his lifelong fascination and tormented investigation of whether the self can be accessed, whether words or drawings best capture meaning, and whether communication is possible at all. As an artist and writer, he is radically divided, torn and trying to unite all of his conflicting convictions and disparate aesthetic projects.

While Michaux ultimately rejects the Surrealist movement as a viable answer to his desire for a form of linguistic universalism, it’s nevertheless tempting to view Thousand Times Broken as an extension of surrealist experimentation with automatic writing, undertaken a few decades after the fact; all the texts in the book were created during Michaux’s multi-year experimentations with mescaline, and he seems to be trying to access his unconscious through drugs, and to illustrate it in as unfettered a way as possible. But, as Conoley tells us in her indispensable introduction, Michaux felt that the human hand and even language itself was too slow to capture thought; he rejects the notion of automatic writing as impossible, even as he continues to experiment with a version of it. Much like the project of translation itself, Michaux seems to be devoted to something for which failure is inevitable: translating the within of the inner self to the without of a medium, be it language or drawing. And ineluctably feeling frustration and discontent with the results. All three texts in this volume return to Michaux’s sense of inadequacy, of falling short.

Minimal in size and length, Thousand Times Broken is an inventive and aptly hallucinatory collection of texts and images that offers a glimpse into the astonishingly un-minimal oeuvre of one of the twentieth century’s mysteriously obscure giants. Published alongside the French original text, Conoley’s work is an act of devotion to this looming figure of international art and letters, and captures the uncanny and occasionally violent pilgrimage undertaken by the “rationalist mystic” artist. Michaux is a character of intimidatingly prodigious creativity, having produced more than thirty books and over twenty thousand paintings during his life (1899–1984). His hypnotic visual art has appeared in prestigious museums throughout the world, and he has been internationally lauded by the likes of Borges, Ginsberg, and MC Solaar.

Three separate texts appear in this volume: “Peace in the Breaking,” “Watchtowers on Targets” and “Four Hundred Men on the Cross.” Written between 1956 and 1959, the texts are wildly different, and share the pages of this book due to the role hallucinogens played in their creation. Conoley’s introduction to the works is an absolutely essential guide; on their own, the hybridized poetry/prose/print texts might seem a bit impenetrable to anyone other than a committed Michaux scholar. With enough background to navigate the three titles, however, the reader is solidly immersed into Michaux’s anxious and dreamlike world. Conoley is our immensely capable guide, demonstrating an incredible grasp on not only the text, but on Michaux’s own angst-ridden ideology and personal history. From a text that would be insurmountable in the wrong hands, she has delivered a careful and close translation that captures the subtleties of Michaux’s artistic and linguistic quest for an impossible metaphysical unity.

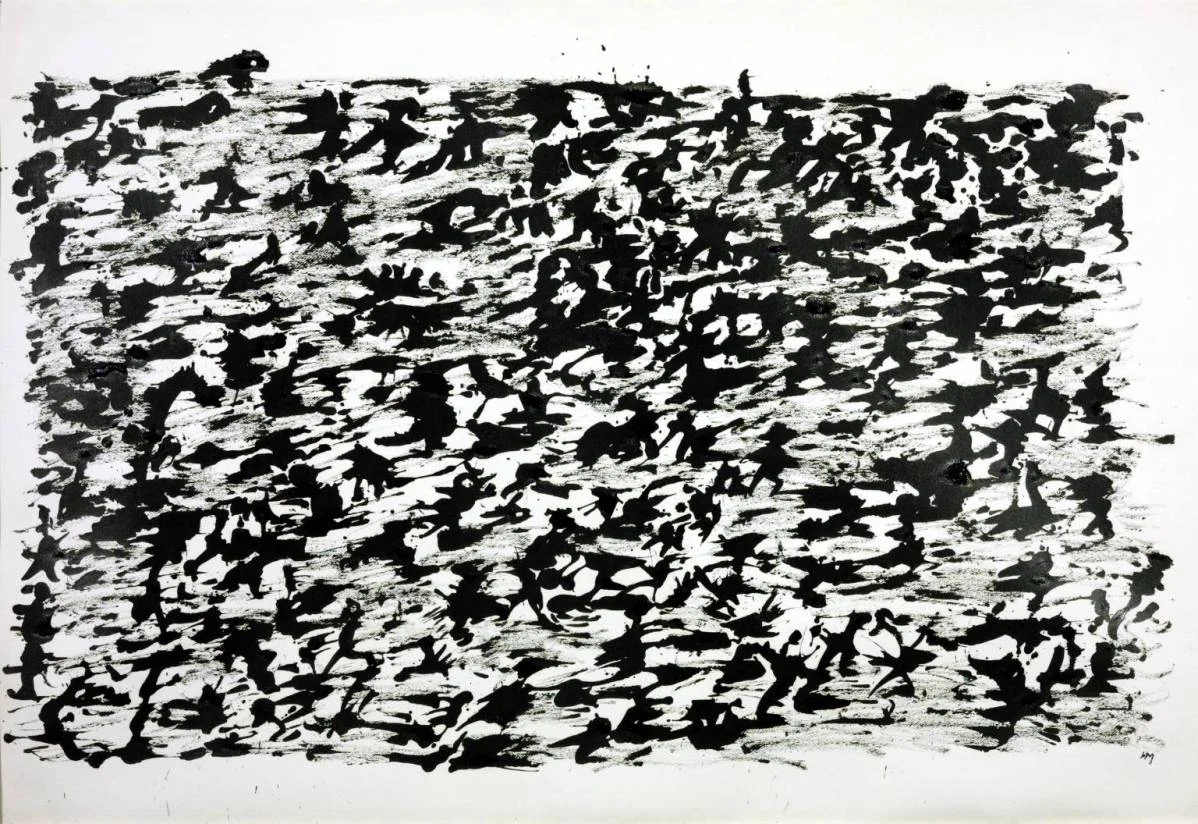

The first text, “Peace in the Breaking” (1956) opens with a handful of black and white images that Conoley describes as “spine-like.” Within each frantically etched furrow, there appear to be letters and fragments of words, unintelligibly scribbled and begging to be decoded. Some of the prints look as though they conceal a form of hieroglyphics nestled within the abstract scrawl. In the essay-like prose section that follows, called simply “Meaning of the Drawings,” Michaux finds himself endorsing a more “natural” way of writing, ostensibly closer to what the Chinese have adopted:

A fact worthy of digression, the Chinese, who have had for a long time an inclination, a true genius of modesty for imitating nature, following the direction, the pace of natural phenomena and remaining joined in sympathy with them by some sort of poetic intelligence, have, conversely to nearly all other peoples on this Earth, conceived and used a type of writing that follows thought from top to bottom along its natural outlet.

A fact no less curious, words there are of characters, firm, fixed signs that are above all made to be seen. And little or no syntax. Subterranean grammatical corrections to be guessed at. What their words present above all is a picture, a picture made of fixed, invariant pictures. Still close to visionary thought, the original appearance of the first phenomenon of thought. But let’s abandon this. Languages all so strong, so possessing.

Though Michaux seems willing to flippantly abandon the notion here, the concept of “fixed signs made to be seen” has regularly occupied his imagination in the past, and will continue to haunt him for the rest of his career. In 1922, the year in which he first starts writing, Michaux calls for an ESPÉRANTO, a universal written language shared by all the writers of his generation. Michaux’s first visual work is “Alphabet” (1925), in which he creates a series of personal ideograms that resemble letters of the alphabet but aren’t, that should read like words but don’t. As Conoley points out in an interview, that instead of arriving at this point after years of aesthetic experimentation this is “where Michaux starts. Michaux wanted to find a universal language somewhere between writing and drawing, and he knew this right away. That, and a desire to delve into the unconscious, give his work an extraordinarily consistent singularity of vision.” This desire for a universal language unites all three texts in Thousand Times Broken, and is a theme Michaux returns to again and again. This compulsion for reconstruction or reunification, represents Michaux’s unfailing idée fixe, the obsession that seems to underpin all the texts in this volume and a notable percentage of the vast oeuvre produced during his multi-decade career.

Michaux’s writings are steeped in an affect of isolation, and it’s hard not to read his desire to achieve a universal language as a profoundly lonely plea for true communication, another project that seems destined to fail. Michaux is on his own, separated from his mother tongue, his native country and from his peers, sometimes isolated even from himself. Later on in “Peace in the Breaking,” he writes:

Michaux, like many exiles, had a conflicted relationship to his home country. Born in Namur, Belgium, he emigrated to France in 1924, and was finally given French citizenship in 1955. Michaux rejected the French National Prize for Literature, which he won in 1965, but his writings have been given what the Guardian calls “the full Gallimard treatment,” confirming his status in the national canon of his adopted country.

Though French is the language he writes in, it is not precisely his mother-tongue, or, more specifically, not the language his mother speaks: she speaks Walloon, a dialect. At the age of seven, he is sent to a Flemish-speaking boarding school in the countryside, an experience that fills him with shame and disgust. In his strange autobiographical chronology/poem of his life, “Some Information about Fifty-Nine Years of Existence” (published in English in the comprehensive anthology Darkness Moves) Michaux documents his life in the third person, and sketches out early experiences with multilingualism. At a Jesuit School in Brussels, he becomes interested in Latin, “a beautiful language, which sets him apart from others, transplants him: his first departure. Also the first sustained effort he enjoys.” Already, language is something that separates him from those around him. Language becomes a voyage, a journey, a distance to cross. In his early experiences with Latin translation, the seeds are sown for the travel writing he undertakes during the next decades of his life (Ecuador, A Barbarian in Asia).

After the First World War, Michaux writes in French for the first time. In his poem, he writes: “A shock for him. The things he finds in his imagination! . . . But he rejects the temptation to write; it could turn him away from the main point. What main point? The secret that, from his earliest childhood, he has suspected might exist somewhere. People around him are visibly unaware of it.” Instead of providing access to the “the secret” (of the unconscious? of a universal language?) writing initially represents for Michaux a threat; he fears it may obscure the truth of what he is seeking. Driven away from language, but unable to resist the desire to write, Michaux finds himself caught between, in limbo.

The second text in Thousand Times Broken, “Watchtowers on Targets,” is a collaborative effort between Michaux and Chilean artist Robert Matta. Matta and Michaux shared a deep affinity as visual artists; this profound connection lasted until Michaux’s death, an event that left Matta bereft. For “Watchtowers on Targets,” Michaux’s text serves as a type of narrative or caption to Matta’s abstract, cartoonish images. This section, like the first, is loosely divided into three components. The first two are responses to Matta’s images, and present charming word-tableaux of bizarre scenes. Though not strictly narrative, each one tells a little miniature story: “Around the violated shelter, there was hurried activity. Everyone wanted to attend the apoplexy of the swan.” Each contains a small mythological world, filled with centaurs and larvae, exotically named characters, dogs, water. In the section called “Correspondence,” Michaux writes “cards” for Matta’s illustrations. These are wild, humorous fragments of an epistolary exchange, seeming to be one half of a set of postcards sent back and forth. The series ends with a rather brutal falling out, with disembodied tongues hanging on the floor. Communication severed, as always.

The third text in “Watchtowers on Targets” shifts the call-and-response game between the two artists: “In Space the Fragmented Life,” Matta illustrates Michaux’s poems. Appropriately, the poems in this section are all about numbers, lists, enumerations. The poems read like mystic numerology, an oracular text filled with buried meaning and hints of the future. Every character in these poems is broken, divided:

Here again Michaux is tormented by the irreconcilable, by his need, both spiritual and intellectual, for everything to come together, to be “one.” The only reconciliation that seems to be on offer is the outrageous pairing between Michaux and Matta, interdependent artists who are attempting the impossible project of “Correspondence,” of communication. The section concludes, after a litany of incessant, infinite, ubiquitous indeterminacies (and the thousand times broken mirror of the title) with an italicized fragment: Sun that is able to reunite

In his autobiographical poem, Michaux writes of his early years spent at sea with a wistful nostalgia, a contentedness that seems out of character at the very least: “Amazing comradeship, unexpected, invigorating. Bremen, Savannah, Norfolk, Newport News, Rio de Janeiro, Buenos Aires.” He is happy on the ocean. But, circumstances eventually compel him back to land: “All over the world, ships (formerly used to transport troops and food) are being laid up. Impossible to find a job. He is obliged to turn away from the sea. Back to the city and people he detests. Disgust. Despair. Various professions and jobs, all poor and poorly deformed.” Michaux is happiest in the middle, travelling the ocean in between locations. He is constantly caught straddling worlds, reluctant to jump to one side or the other. In taking the mescaline that inspired Thousand Times Broken, he is enticed by the possibility of accessing his unconscious but remaining fully conscious, rational. He is a former medical student turned poet. He is a writer and a visual artist. A speaker of Flemish and of French. A Catholic and an unbeliever. Michaux seems capable of living only in the middle, of inhabiting a bifurcated space. Only his body can join together these fragments, inscribing with his hands, purifying his body. Though not precisely a martyr, Michaux’s work is a passion, in the Christian sense, a physical and spiritual ordeal that may or may not lead to a sort of salvation. In the graphic title of “Four Hundred Men on a Cross,” Michaux himself is fixed to the head of the cross, where the crown would be; he is nailed there.

This final section is the most anguished and the most inventive of the three texts of the volume. In “Four Hundred Men on a Cross,” Michaux attempts to come to grip with the loss of his Catholic faith and narrates a series of executions. Margaret Rigaud-Drayton describes the poems here as “graphic writing”; the typography of the poems is shaped, often as crosses. These concrete poems depict one crucifixion after the other, most of them painfully reluctant, unwilling: arms that have “positively fled out sideways,” hands that refuse to be tied down, even an uncooperative suffering cross. Physical pain is more present in this poem than the others, as though Michaux himself is wincing through this process; more than in any other section, we are reminded of the material sensation of taking mescaline, of the discomfort of ingesting something so disruptive. In one section, he states that if he were a seminary director, he would require his seminarists to execute drawings of “the crucified man” over and over, a procedure that would “teach me more than the confessions of a whole year, those facile confessions in words.” But of course, Michaux has been doing just that, visual drawings and word-drawings of the crucifixion, repeated again and again as some sort of penance. In the final segment of the volume, he asks:

This rather bleak conclusion is what we’ve come to expect from Michaux. Having undertaken a journey, a physical expiation, and having meticulously recorded it with his artist/rationalist dedication, he tosses it away, convinced it was doomed from the start. His almost Beckettian belief in the certainty of failure (of words, of art) makes his lifelong prodigious output appear a little manic. But the intensity of Michaux’s desire to truly say something causes Thousand Times Broken to radiate with a fierce and humorous humanity; it is a portrait of a flawed creature, seeking and sometimes hitting upon the edges of the secret that Michaux has spent a lifetime chasing after.

Caite Dolan-Leach is a writer and translator. She currently lives in Cape Town.

Translation © copyright 2014 by Gillian Conoley. Reprinted by permission of City Lights Books.