|

(Photo: Danny Kim) |

According to one of Jonathan Safran Foer’s favorite essays, John Ashbery’s 1968 classic “The Invisible Avant-Garde,” what makes innovative work exciting is that you’re never sure it’s any good. “Recklessness is what makes experimental art beautiful,” Ashbery wrote, “just as religions are beautiful because of the strong possibility that they are founded on nothing.”

Foer, enjoying a hummus wrap a few blocks from his NYU faculty office, says he believes such works have to be either “great or terrible. They require a leap of faith.” The author’s own first two novels, while hardly avant-garde, do walk a deliberate line between cuteness and horror, taking the reader for a giddy carnival ride, often exhilarating if occasionally nauseating. His latest project, Tree of Codes, may be divisive for a new reason: It’s physically hard to read.

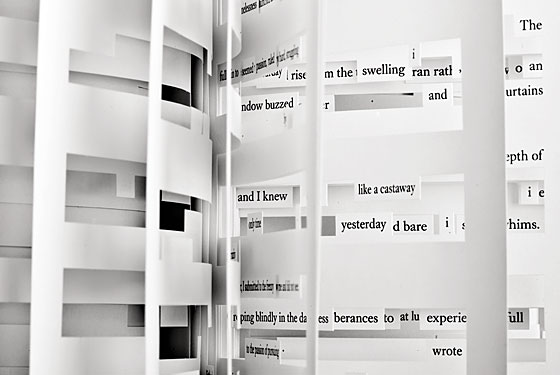

Imagine a book—in this case the 1934 novel The Street of Crocodiles, a surrealistic set of linked stories by the Polish Holocaust victim Bruno Schulz—whose pages have been cut out to form a latticework of words. The result is a new, much shorter story and a paper sculpture, a remarkable piece of inert, unclickable technology: the anti-Kindle. Reading it is a little like going through an FBI document full of blacked-out passages, except that the excised portions are now holes through which you get glimpses of subsequent text. The format slows your eye down (though it helps if you slightly lift the page you’re on), but the book is so brief that it can still be read in half an hour.

Two years ago, a fledgling British publishing outfit called Visual Editions e-mailed Foer with the message “We can’t pay you, but you can make anything.” The company had envisioned something along the lines of graphic renderings of Foer’s novels, but he had a more ambitious idea. “I’d thought a lot about die-cutting,” says Foer, referring to the industrial process of punching patterns into material. He considered a few options, including an encyclopedia. “But everything I thought of felt like an exercise. When I started thinking about Street of Crocodiles”—whose lush, odd turns of phrase offered a near-limitless palette of words—“I started to feel invested in the project.”

After months of trial and error, Visual Editions has been able to produce a delicate object resembling a book. The process was so complicated that to break even, the publisher had to price the paperback at a hardcover-level $40. But the marvel is that it’s been mass-produced at all. “You wouldn’t want most books to look like this,” says Foer. “But it’s not a museum piece.” What is it then? First of all, Tree of Codes is a story—a laconic, poetic narrative about a grieving family—but one that, Foer will be the first to admit, could never work on its own. “It’s a way of remembering something about books,” he says. “I think there’s going to be something that happens now, where books move in two directions, one toward digitized formats and one toward remembering what’s nice about the physicality of them.” Several tech-publishing gurus have opined that books might follow Radiohead’s In Rainbows model: downloads at low prices, along with limited-edition collectors’ objects for hard-core fans.

Foer thinks a lot about such scenarios. A favorite book of late is Jaron Lanier’s You Are Not a Gadget, a technophile’s screed against the restrictive hive-mind of the Internet. “It made my hair stand on end,” Foer says. “Writers now are putting total faith in designers at Apple and Amazon. It’s almost like a race-car driver having no input into how cars are designed.” It’s not enough, he thinks, for authors to tell stories in the same old ways, even as publishing transforms. “We happen to be going through a conservative moment within this conservative art form,” he says. “A move back to the nineteenth-century novel is seen as radical progress.” Is he talking about Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom? “I actually really like that book, but it’s not the only kind of book.”

At NYU, Foer preaches what he practices. The class he’s teaching this semester to NYU undergrads is called “Impossible Writing.” (He was allowed to create whatever class he wanted; his colleagues include Junot Díaz, Zadie Smith, and Ashbery.) Students are told to come up with, say, a “site-specific” piece of writing, or an oral story, or a plaque from an imaginary museum. It sounds like exactly the kind of class Jonathan Safran Foer would teach: Inventive, for sure, but verging on Gimmicks 101. Typographical play is something for which he makes no apologies—remember the flip book (depicting a man falling up alongside one of the burning Twin Towers) that ended his second novel, Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close. Foer counters that only in writing do such incursions from other art forms draw much attention. Text is inserted into paintings, paintings into opera, and critics don’t bat an eyelash. “Literature has drawn a funny perimeter that other art forms haven’t.”

All that said, Foer predicts the novel he’s now working on—after a few years off raising two kids with novelist Nicole Krauss and writing the nonfiction Eating Animals—will have no such bells and whistles. But it will be even more aggressively tragicomic, full of “emotional dissonance” as hilarious and terrible things happen at once. “I feel like I’m taking bigger risks,” he says. “They’re just not formalistic risks.” As for the more distant future, all bets are off: “Life is long, and I want to try a lot of different things.”